The past couple days have brought startling news from the jazz world:

First, last night's announcement of David S. Ware's passing at the relatively young age of 62, circulated by Patricia Parker and reported by various sources, including Peter Hum's blog.

Second, the publication on Wednesday, via Do the Math, of what can only be called a manifesto from the self-dubbed Rockjazz piano star Eric Lewis (who performs as ELEW). It's a remarkable piece of writing. AccuJazz.com dubbed it "really engrossing straight talk"; I'd second that and add that it's also stupendously witty.

It seems odd to link word of a death with any other bit of information; I hope I don't sound crass in that regard. At the same time, I'd be lying if I said that the two figures didn't converge in my mind when I heard about Ware. Let me explain:

When I think about Ware, I think about beautiful music: e.g., an intimate Brooklyn solo concert I had the privilege to attend in March of 2010 (released last year on Aum Fidelity as one half of Organica), or my favorite Ware record, 1979's Birth of a Being, as far as I know the only officially released document of the collective trio known as Apogee, with pianist Gene Ashton (later to be known as Cooper-Moore; read his fascinating reminiscences re: the group—including an account of opening for a band led by Ware's friend Sonny Rollins at the Vanguard—a little more than halfway the page here) and drummer Marc Edwards (still kicking ass in NYC on a regular basis). Respect to Ware's celebrated quartets of the ’90s and aughts, but this early release has captured my imagination more than any other DSW release. To my ears, it's probably the single greatest document of second-wave free jazz. Happily, a blogger has uploaded it to SoundCloud; the pleasures of this music, that heartbreaking, hymnal, post-Ayler lyricism, which gradually splinters apart, like a homey cottage in the path of a tornado, are plain:

But when I think about David S. Ware, I also think about what it means to have a career in jazz. The discussion of how musicians operating in this genre can make a decent living while retaining integrity is a constant one, which seems to flare up about once a year at least. (See also: another recent post by Peter Hum.) While I doubt that Mr. Ware was a particularly wealthy man in the grand scheme of things, certainly it's fair to say that he was one of the more visible jazz musicians of his generation (maybe "peer group" would be more accurate). I don't think I'll ever forget this Gary Giddins assertion, via a July, 2001 installment of his Weather Bird column in the Voice:

"Let's be bold: The David S. Ware Quartet is the best small band in jazz today. I realize that I will almost certainly hear another quartet, or trio or quintet or octet, this week or next, that will make me want to backpedal. But every time I see Ware's group or return to the records, it flushes the competition from memory."

I didn't know enough about the state of jazz in July of 2001 to particularly agree or disagree with Giddins's assertion, but I admired the ballsiness of the statement. (Looking back on the period now, I'd probably give the nod to Tim Berne's then-nascent Hard Cell band, later to be expanded into Science Friction.) But whatever my own feelings about Ware's music, I had an understanding that he was something like the Michael Jordan of this world of Vision Festival–affiliated NYC free jazz that I was just then starting to discover, the member of that crew who had achieved some measure of niche-transcending fame. Around that time, I remember visiting the apartment of a not particularly jazz-fixated friend and spotting a copy of Ware's 1998 Columbia debut, Go See the World, in his CD collection. It was only later that I came to understand how exactly it was that Ware had achieved this name-brandedness, which began to snowball around 1994, thanks in large part to the passionate advocacy of current Aum Fidelity boss Steven Joerg, then working at the Homestead label. (Brad Cohan's 2011 interview with Joerg is a valuable primer on all this: "The idea of signing the Ware Quartet was a bit of a stretch, but I convinced [Homestead]," says Joerg. "The first record we did—Cryptology—ended up being the lead review in Rolling Stone.") I have a memory of Ware's 1999 Columbia record, Surrendered, as being a bit tamer, but listening back to the two now, I realize that both were/are marvelous anomalies, HTGMLPCFJRs! (honest-to-God major-label post-Coltrane free-jazz records, i.e.) I look forward to getting better acquainted with these albums.

I can't speak to the nitty-gritty details of Ware's Columbia signing; it would be fascinating to read an interview with the A&R rep who was responsible for that deal. [Update: Mark Stryker informs me it was none other than Branford Marsalis! I had no idea. Peter Hum points the way to this valuable document: "Branford said don't change a thing," says Ware. Given that Wynton figures into the ELEW saga, it makes me wonder how many jazz success stories of the past 20 years or so don't include the Marsalises in some respect.] But details aside, and whatever the net effect of this episode on the Ware's quality of life then and later on, one has to marvel at and respect the fact that DSW busted through a glass ceiling in a certain respect. Obviously the scale is vastly smaller, and the analogy is iffy due to the fact that unlike Cobain & Co., Ware's signing did not pave the way for a whole wave of like-minded indie artists, but it's hard not to see Go See the World as the Nevermind of American free jazz, a record that mainstreamed, or at least attempted to, an inherently underground aesthetic without masking its essential rawness—and a record that even celebrated that rawness. It seems to me, in other words, that Ware succeeded in the marketplace without compromising in the slightest, that Go See the World is more or less the next record his band would've made for Aum Fidelity had Columbia not stepped in. If you think about it, that's pretty damn cool.

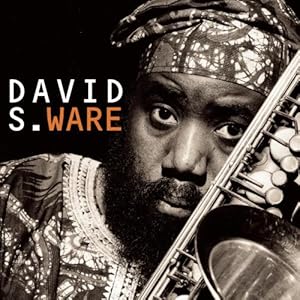

So when I say I linked Ware and Eric Lewis in my mind, what I mean is that, having just read Lewis's disarmingly candid account of how he forged a thriving career in music—proceeding at first through conventional jazz channels and then later fashioning an arena-ready aesthetic built around improv-heavy covers of well-known rock songs—I couldn't help thinking about how these two figures might have regarded one another. Ware's circle was obviously not the same one (i.e., the Wynton Marsalis orbit) that Lewis occupied before rebranding himself—and if you've read the piece, you know that I mean that phrase very literally—as ELEW. But these are obviously two extraordinarily skilled musicians who labored for years over their respective brands of jazz and managed—again, each in their own respective ways—to carve out a place for themselves in the jazz-unfriendly marketplace. (And even Ware, whether consciously or not, was a brand: It's hard to look at the album cover above and argue that there wasn't some image-building going on there.)

I'm not making any value judgment here. I haven't heard enough of ELEW's music (really, just a cover of "Mr. Brightside" at a Jazz Foundation of America event a few years back) to give an informed opinion on it, and my knowledge of Ware's work in the ’90s and 2000s is spotty as well. But it is fascinating to think of these two figures, both "stars" in a certain sense, one of whom won a degree of fame (and even a major-label deal) working in one of the most seemingly "difficult" subgenres in American music, i.e., post-Coltrane free jazz, without altering his core values in the slightest, and the other, who strategically retooled his entire aesthetic, grafting his love for and command of jazz onto a commercially viable "hook" and succeeding beyond just about any contemporary jazz musician's wildest dreams (touring with Josh Groban, etc.). There is no right path. Ware seemed entirely in love with his artistic pursuit, and Lewis, in his own way, seems to be in love with his. Yes, in the latter case, art intermingles more straightforwardly with commerce, but as anyone who has ever tried to make a living at anything creative (writing, ahem) could tell you, it pretty much has to at one point or another, so why not be open about that fact?

Again, I'm not advocating for the ELEW model, nor am I criticizing it. I'm simply stating that it seems to have worked for him, in the sense that he appears to be happy and fulfilled doing what he does, over and above the fact that he's making a good living doing it, and that that is in many ways the definition of success. Ware succeeded too, in that he reached many more listeners than 99 percent of the other free-jazz musicians who have ever lived. Think of the great John Tchicai, who passed away recently at the age of 76. I don't have encyclopedic knowledge of his work (I will say that I adore the early New York Art Quartet works), but I feel comfortable asserting without verifying it first that Tchicai never landed the lead review in Rolling Stone—or, for that matter, toured with Josh Groban. Everyone loves an unsung hero, but sometimes it's worth thinking hard about the players, like Ware and Lewis, who have "made it," and about why and how they did: how much, i.e., was due to their own deliberate efforts, as in the case of Eric Lewis reimagining himself as ELEW; how much was due to tireless advocates, e.g., Steven Joerg in Ware's case; how much was due to the conditions of the marketplace during a given period, etc. As jazz fans, we're bred to be suspicious of success, of visibility, etc., and certainly many of the music's brilliant statements, especially since the ’70s have been made underground, as it were, but we should celebrate the fact that certain artists in the field have managed to climb a little higher, to position themselves a little closer to the popular sphere, to go see the world, as it were. As Lewis suggests, there are lessons to be learned even from Kenny G.

I don't mean to reduce Ware's sad passing to an occasion for soapboxing; all I mean to say is that, with Lewis's fascinating career arc on my mind, I couldn't help but muse a bit on art-and-commerce as it pertains to jazz. May DSW rest in peace, and may ELEW continue to thrive on his own terms.

This is beautiful, Hank. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteHi Hank's readers,

ReplyDeleteHere are my two interviews with David S. Ware for The Jazz Session:

http://bit.ly/l7NZM1 (2010)

http://bit.ly/R5XS45 (2011, with William Parker, Cooper-Moore and Muhammad Ali)

Jason