UPDATE, 5.8.2011: A few days after posting this appreciation of Strange Meeting, I received a nice e-mail from David Breskin, who produced the record. He also contacted Steve Smith and he very kindly offered to a) fill us in on the details of this session, and b) correct one longstanding misconception, namely that—as mentioned below—Strange Meeting was originally intended as a quartet date with Julius Hemphill. Not true at all, it turns out!

Breskin followed up a few days later with a fascinating account of the making of the record. As you'll read below, there was nothing accidental about it; Strange Meeting was a true old-school PRODUCTION, complete with rehearsal, strategic preplanning and a real aesthetic backbone. (My sense is that there aren't a whole lot of jazz records being made this way anymore.) Breskin's text doubles as a fascinating insider's perspective on the NYC jazz scene in the ’80s. It's essential reading for any fan of that period, of Strange Meeting in particular, of the musicians involved in general, or for anyone interested in the way a producer can act as a true collaborator, setting parameters that liberate rather than constrict, ultimately yielding an ALBUM rather than just a collection of performances. Breskin's text, edited and fully approved by him, appears below my post."I thought Shannon’s playing might do something interesting to Bill and that Bill’s playing might do something interesting to Shannon, and that Melvin would be a perfect fulcrum and shifting counterweight: suitably fierce but appropriately subtle and supportive when need be and no road hog he. Anyway, that was my hope. I thought this could be a cool band, and Shannon always used to say, 'Nothing beats a failure but a try.' So, why not?"

—David Breskin on

Strange Meeting/////

I wrote a little while back about the idea that free jazz ought to be documented in the studio as well as onstage. Been thinking again about that the past few days, while immersing myself in

Strange Meeting (Antilles), the lone officially released recording by Power Tools, the trio of Bill Frisell, Melvin Gibbs and Ronald Shannon Jackson.

I have heard from Steve Smith (who,

as you can read here—scroll down to the 1987 section—regards

Strange Meeting as a desert island disc and a perfect record) and other sources that this January, 1987 record date was originally scheduled to be led by Julius Hemphill. He didn't show, though—apparently due to illness—and a new scheme was quickly hatched. I'm not sure if the date was supposed to be these three gentlemen *plus* Hemphill or if one of them was called in to replace him, but at any rate, what you have here is the only in-studio meeting of Frisell, Gibbs and Jackson, and it is indeed a strange one. [

NOTE: Hemphill was never a part of this date. Please see intro and addendum to this post for details.]

And really the strangest thing about it, given the aforementioned haphazardness of its organization, is how incredibly *together* it all sounds. You might expect some sort of free blowout: "Ah, fuck it—let's just improvise and roll tape." That is not what this record is at all, though. It is an honest-to-goodness full-length

LP, paced as intelligently as any rock classic you could name.

You would honestly think this lineup had been together for years. All of the members contribute pieces, and the writing is more or less evenly split: three pieces by Frisell, three by Gibbs, two by Jackson, one collective jam and one cover (yes, "Unchained Melody"). This, to me, is the formula for success in jazz, and maybe even rock too, though it's much rarer. (Descendents/ALL comes to mind; their albums have always been everyone-pulls-their-weight-both-compositionally-and-instrumentally affairs.)

I'm skirting around the music itself, maybe because it's such an enigma. You can't typify what this band sounds like—you have to hear the whole record, really. Gibbs's compsitions, "Wadmalaw Island" and "Howard Beach Memoirs," just floor me. The former is a beautiful, alien quasi-ballad, held together by a Latin-ish vamp. Frisell's sublimely ’80s-ish reverb is just the right thing for it. The band sort of slinks along, doling out its energy gradually. You may never have heard Shannon Jackson play this sensitively. It's like undersea

Miami Vice jazz from Pluto. And then Frisell brings out the distortion, and the poetry becomes a bit scary, almost Sharrockian. You think of synthesized seagulls, like in Don Henley's "Boys of Summer." This, to me, is the true ’80s jazz. Lush, sorta-dated-but-you-don't-care sonics mingling with heartbreak. But the real-time improvisation is right there—it's not frosted over with stiff arrangements or soupy sound.

The trio does hectic scribble just as well as it does noirish emoting. Jackson's "A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing" features a tumbling, brief, Ornette-ish head that gives way to a magical kind of clunked-out funk that only Shannon could provide. I would venture to say that his drumming is better here than it ever was in Last Exit. In that band, Shannon tends to go for the broadest gesture, either the martial, about-to-blow ramp-up or the boneheaded electric-blues beat. Here, though, he's actually playing free jazz, more or less, while also keeping the beat. Gibbs's chords jut out crudely, Frisell screams one minute, whispers the next (I tend to hate overly pedal-effected guitar, but Frisell uses pedals like a true surrealist on this record) and Jackson tumbles and exclaims. The beat is somewhere there, but it's not explicit. The band heads out the cargo hatch into space but they hold onto the line. What astounds me is that the piece is only three and a half minutes, but you get a real without-a-net free-jazz feeling in between the bookends of the heads, which themselves give off a very authentic, four-handcuffed-men-being-jostled-violently-around-a-room Ornette-head vibe. It's a true fusion of pop production practices—get in and get out quick—and free-jazz abandon. Great taste

and less filling.

And this is what I mean about free-jazz sometimes jelling really well in the studio. Sometimes you don't want to hear a 30-minute live blowout. Sometimes you want to hear the chaos tastefully integrated, in a context you want to play and re-play. Sometimes limits are good.

There's so much else to love on

Strange Meeting. I honestly don't know if there's a weak track. I'm spinning the collectively improvised track, "The President's Nap," right now, and as with a lot of Power Tools material, it sounds like the subtler cousin of Last Exit, not as balls-out aggressive but probably more fulfilling on a purely interactive level. Shannon starts out with one of those jaunty, Last Exity marches, Gibbs hops on the train, and Frisell tosses out waves of pure sci-fi sound. Then the whole thing tilts toward something scary and nuclear-sounding, like a parched landscape about to blow. The band is moving all at once, like a miasma in the sky, some sort of hot, creeping menace. The climaxes are hectic and—thanks in part to the outstanding recording quality—vibrantly detailed. It's not just free sound, not just noise. It's deep-listening abstraction, swirling together funk and rock and free jazz and technology and Michael Mann–ish ’80s humidity. You hear this and you feel almost embarrassed for anyone who was still chowing down on old-school, meat-and-potatoes acoustic free jazz circa ’87. This is a music of its time, the best kind in fact. There's a certain mist of cheese swirling around

Strange Meeting, but the playing is so goddamn wholesome, so real and right on, that it just becomes part of the joy. It's an if-this-is-wrong-I-don't-want-to-be-right type of thing.

I could go on and on. Frisell's "Unscientific Americans" is another sci-fi Ornette-style tumble. I don't know Prime Time too well, but honestly this band sounds like what I'd *want* Prime Time to sound like, a true electrifying of the skittery, headlong O.C. vibe with none of those bummer boxy funk rhythms. Frisell is basically playing the laser gun here. The song is all the gnarlier, all the more "fuck you" because it's three minutes long. I've been spinning

Strange Meeting all weekend, but I find myself appreciating it even more right now. I can't emphasize this pop/free-jazz vibe enough. It's like a not only benevolent but actually mutually beneficial ’80s-izing of avant-garde jazz. It's concise but it's not tidy. Sure it might be cool to hear this band stretch out for 40 minutes or so, but they want to play *songs*, start from coherence and then explode the universe in the time it would take to run down a bebop tune.

I wish I could stream Gibbs's "Howard Beach Memoirs" for you above. It's a parched, steely line, with so much internal poetry and narrative contour. I think of a (nonexistent) Michael Mann cowboy film, Dylan Carlson from Earth playing with a rhythm section that shifts like magma under his feet rather than plods. Frisell lets the alien spiders in after the head. Into the tech-jazz vortex. I think of those old, big, clunky, white-rimmed VHS tape boxes that snapped shut. Instead of snuffing the jazz out like some pillowy ’80s production can, the *casing* of this music, its presentation and milieu and delivery system, is friendly to the aesthetic. Shannon Jackson solos at the end of "Howard Beach," punching holes in the sky with his close-miked arena-rock toms.

And there at the end of it all is "Unchained Melody," romantic and wired all at once. Did the producer suggest it? Who knows, and who cares? You can in fact make a *record* of this music. You can trim it at the edges and not cut out what makes it tick. That way, you can listen again and again.

/////

*Sadly

Strange Meeting does not appear to be available for legal download. You can, however, order a pricey autographed (!) copy direct from Ronald Shannon Jackson

via his website. (There are a few Power Tools boots there as well, in addition to a bunch of intriguing Decoding Society selections.)

*

Here's a nice clip of Power Tools playing Frisell's "When We Go." Check out this comment someone left: "Ronald Shannon Jackson and Bill Frisell are about a millisecond from obliterating into sun particles; some of the most visceral playing with refrain and control. Fortunately, Melvin's got the weight of the world within his thumb alone to keep the gamma rays from shooting skyward..." Nice.

*Here's

Destination: Out on Strange Meeting back in ’08, featuring helpful context re: "Howard Beach Memoirs."

*

Strange Meeting begs the question: What are other great fruitfully ’80s-ized (i.e., not just made

in the ’80s but true products

of the ’80s) avant-jazz studio recordings, albums on which the then-modern production style or record-making philosophy enhanced rather than dulled the impact of the music?

*Also: I don't know the Frisell, Gibbs or Decoding Society discographies all that well. Are there other records by any of these entities that get at the

Strange Meeting vibe, or is this record really as anomalous and gemlike as it seems to be?

*Also, what do people know about the Antilles label? Of the catalog

listed here, I only know the Air and Braxton records, but I'm very intrigued. What's up with that White Noise record (which features Paul Lytton)?

/////

A Few Notes on Power Tools and Strange Meeting by David Breskin5.6.2011

I met Shannon Jackson in the summer of 1979, when I was an intern at

The Village Voice. I conned Bob Christgau into letting me write some

Riffs—it was hardly part of my job—but I wrote on Terje Rypdal, Bootsy Collins, Oregon and Weather Report, if memory serves. (That may be the first time Terje and Bootsy have ever been found in the same sentence, and if so, this would mark the second.) In any event, I met Shannon after one of his gigs at the Public Theater that summer—he was playing with Blood Ulmer, David Murray and I think Amin Ali was the bassist. And I went back to Providence for my senior year in college and also my last year as jazz director of WBRU (under the name “Spottswood Erving”) and Shannon and I stayed in touch in epistolary fashion, and developed a strong connection.

After college I moved to New York City in the fall of 1980 and ended up producing The Decoding Society’s

Mandance and

Barbeque Dog, as well as Shannon’s own “solo” drum record,

Pulse, bringing along my poetic mentor from college, Michael S. Harper, to collaborate with Shannon on a few tracks. In the fall of 1981, I went on a long European tour with the band and got to know everyone pretty well, including, of course, Melvin Rufus Gibbs and Vernon Reid. I also met Bill Frisell in the early ‘80s and was absolutely wowed by his playing: I thought he might be the “Thelonious Monk of the Guitar” or something like that. I got to know Bill, grew fond of him, and in due course produced a collision between him and Vernon,

Smash and Scatteration, recorded in the winter of 1984 and released in ’85. My internal code for that project was: “Mr. Rogers Meets The Wild Child” though originally that record was intended to be for a trio, with John Scofield being the third guitarist. We just couldn’t make the schedules work.

Over those years, I’d brought Bill to some Decoding Society gigs and brought Shannon to come see Bill play. They were full of mutual admiration. As different as their own music was, they are both, in a sense,

country, and there was an easy camaraderie and feeling at the start. I remember Shannon saying, upon seeing Bill play for the first time, “Look here! There’s nobody, there’s nobody that plays a melody like

that.” Of course, Bill had heard Shannon’s work with Cecil Taylor and with Ornette, and was really interested in what he was

doing, and Bill also admired Melvin’s playing from the Decoding Society gigs and other downtown things.

I remember thinking: if Marx said he was trying to turn Hegel on his head, maybe I could turn the Jimi Hendrix Experience on its head. A very,

very limited analogy, but hey, maybe the guitar player could be the pink guy and the rhythm section the darker-than-pink-guys. A powerfully inverted triangle. There was a real racial walling-off in the “avant” music community at that time—what was white, what was black, blah blah blah. I found it hateful then, and still find it so, though of course it makes perfect sense historically. Didn’t Ralph Ellison say he was an integrationist because an “integer” is a whole number? Well, I want to be in that number when the saints come marching. Anyway, that was a part of my thinking in making this project, but don’t get me wrong: it was not some kind of overdetermined racial thing—it was about the music. It’s just that I was cognizant of the larger context, and that some people would see it as somehow “strange” and that’s one reason for choosing Bill’s song as the title track, and the album cover art being what it is. Also strange, in a different sense, because Shannon’s music was so

heavy (in weight) and Bill’s was so light, in the sense of ethereal and floaty. I thought this combination might create some heat-generating friction.

I came to the three of them with an idea of a cooperative trio, and making a record as a start. It was always conceived as a trio, a power trio. There was never a horn involved. I don’t know where this story about Julius Hemphill’s involvement came from—you know, that he was was sick and couldn’t make the date, and so an unplanned bare-bones trio recorded spur of the moment. That story is totally, uh, spurious. I’d met Julius at most twice: among other things, he and Michael Harper had collaborated; and for a moment there Bill toured with him in the same band as Nels Cline wouldn’t ya know it?; and Tim Berne, who I was in touch with, was close to him…so it’s not far-fetched. But there was no discussion of Julius being included. And frankly, after the rather horn-heavy Decoding Society, I specifically wanted this to be devoid of hornage, wanted it to be really open, very spacious, where the deer and the fucking antelope roam. I wanted there to be lots of room for Bill, and yet wanted this

not to be one of those trio record where it feels like lead-voice-plus-rhythm-section. I just wanted to couple Bill to this deeply heavy rhythm section and see what kind of freight that train might pull. I thought Shannon’s playing might do something interesting

to Bill and that Bill’s playing might do something interesting

to Shannon, and that Melvin would be a perfect fulcrum and shifting counterweight: suitably fierce but appropriately subtle and supportive when need be and no road hog he. Anyway, that was my hope. I thought this could be a cool band, and Shannon always used to say, “Nothing beats a failure but a try.” So, why not?

We had one planning meeting about the date up at my apartment on 109th street, the four of us. I asked each of them to bring in three tunes. I asked them to bring in songs which would work for

this group and to think of who’d be playing it, whether it was brand new material or something previously recorded. I’d heard some of Melvin’s writing in and around the Decoding Society, really liked it, and wanted him, compositionally, to be an equal partner to Shannon and Bill on the record, and not the less-famous

sideman. I wanted 3 + 3 + 3 + 1 = 10 songs. Five songs a side, and song-length songs, not long jams. The last song (the +1) would be a cover, a great song but not played straight, something radically recontextualized. In the end, Shannon brought in two pieces, “Blame and Shame” and “Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing;” Bill brought in three, “When We Go” and the title track (both of which he’d released on

Rambler in 1985) and the new “Unscientific Americans;” and Melvin brought in three, “Wadmalaw Island,” “A Song is Not Enough,” and “Howard Beach Memoirs.” The title of this last piece was a riff on the popular Neil Simon play (

Brighton Beach Memoirs) which had opened on Broadway in 1983, running though 1986 and was made into a movie that year. Of course, the title and piece specifically refer to the Howard Beach hate-crime of December 1986, when three African-American youths were attacked by a gang of stupid young pink people in Queens. One of the victims ended up badly beaten and one ended up run-over by a car and killed while trying to escape.

If memory serves, the trio rehearsed in Shannon’s studio, I think twice, maybe thrice before the recording. I remember being at one or two of these rehearsals, because I made rehearsal notes to prepare for the recording—something I’ve always done when producing. Anyway, the point is that the project was organized and not “haphazard”: the thing was conceived, bantered about, thought out, rehearsed, and then recorded. For all we knew, this might become a real band and this was just the beginning.

For the date, I picked Radio City Studios, up there back behind the hall, in that historic building. I think I was first there watching John Zorn his “Spillane” piece in the summer of ‘86. Loved the sound of the room, the historic old-fashionedness of the place. Frisell was on that date, as well as Bobby Previte. (A zillion years later—well, fourteen—I’d re-connect with Bobby to produce his

23 Constellations of Joan Miro, but that’s another story.) Anyway, at the “Spillane” session I’d met the engineer Don Hunerberg, who I think was something like a house engineer for that room, and thought he was terrific. So when my normal wingman Ron Saint Germain was not available for Power Tools, we happily ran with Don. (Small footnote: I ended up back in the same room six months later, producing “Two-Lane Highway” for/with John Zorn, his “concerto” for Albert Collins, which also was on the

Spillane record. I’d written a story on Collins for

Musician magazine years before, turns out my cousin in Chicago booked him, and Melvin and Shannon also came in for that date with Zorn and Albert.) Back to Power Tools: I wanted the session to be live, and wanted no editing, no mixing, no overdubbing. It was what it was: like a primary document, like an “early” recording. I wanted the “pressure” of live performance. That band was about a certain kind of

pressure….spatial pressure, temporal pressure, rhythmic pressure, tonal pressure, the pressure of personalities and personal history. I knew we could go for multiple takes of every piece, and just settle arguments that way.

Regarding the group piece: “The President’s Nap.” It happened like this: Shannon was in the studio, warming up, playing by himself, with Melvin and Bill in the room getting ready. I liked what Shannon was playing and told Don to “roll tape” though we were beginning to roll early brutal digital two-track bits, even if tape was what we had in our minds. And I just gestured to Melvin and then Bill to start playing, and they did. The piece developed a beginning, a middle, and an end, just naturally. Game, set, match. It was a free improvisation, completely unplanned and obviously untitled. I offered “The President’s Nap” as a title, given that it’d recently come out in the press—sometime in Reagan’s second term—that the President liked to take a daily afternoon journey to dreamland. Given what Reagan did while awake, perhaps this was not so harmful. The title cracked everybody up, because obviously it spins the music in a slightly comically noirish if not horrifying direction, and it stuck. (Bill’s “Unscientific Americans” was also untitled as of the session, and I suggested that title after the Roz Chast 1986 book of cartoons of the same name. Bill is something of an amateur cartoonist in his own right, and is Roz Chastian himself, it might be fairly said.)

Regarding “Unchained Melody”: yeah, not to sound Monty Pythonish about it, but that was my idea, eagerly seconded by Shannon. I didn’t want to cover a song that was part of the jazz canon and that had been covered extensively by contemporary jazz artists, or even those in our immediate past. And I was also looking for a song that I thought Bill could really just rip into, and

undo. Here was a song that had been covered a gazillion times, but you know, Alex North wasn’t in the Ella Songbooks and wasn’t of any interest to Wynton and his crowd, and it wasn’t like covering yet another Monk or Wayne tune. It was a pop song (though Al Hibbler did it way back!) recorded first as a theme for a mid-‘50s prison movie,

Unchained, hence the “Unchained” in the title. Of course it’s famously a love song, but I was also thinking more abstractly of the Hy Zaret lyric “and time goes by, so slowly / and time can do so much.” Ain’t it true, Shannon, Melvin and Bill? Well, you don’t have to be a musicologist to see how that sentiment might play into this record and this band. Shannon’s point of reference was the Righteous Brothers’ version. For me, it was the Willie Nelson version on his classic Booker T. Jones-produced

Stardust record from 1978. I’d gone out on the road with Willie (I think in 1982) for a

Musician piece, and really came to love his way with standards, and of course Shannon is as Texas as it gets, and I played Willie’s recording for him, which knocked him out. (Willie then led me to Miles Davis, and later to

We Are The World—everything overlaps with everything else—but those are other stories.) Extra-elliptical aside: “Righteous Brothers” became my inside code back-up name for this band, if “Power Tools” couldn’t be used, but that would have been pretty darn “meta” at the time and I can imagine what the legal bills might have been like. Again, this would have gone against the racial stereotyping in about three ways.

Anyway, I am very much a non-musician—I pretty much don’t know anything about music from a technical standpoint—but occasionally I have an architectural or arranging idea and “Unchained Melody” was such a case. I wanted Shannon to open with solo voice, and to play the song as a

march. Always loved Shannon’s way with marches and martial beats and guessed that in hundreds of covers “Unchained Melody” had never been played as a march. (And this was before the U2 cover and the Cyndi Lauper cover and before the song was widely and wildly re-popularized by the movie

Ghost, which didn’t come til 1990. In 1987, “Unchained Melody” was like a great deserted town, you know a place that had been a boomtown in the ‘50s but there wasn’t anybody living there anymore:

The Last Picture Show.) And after establishing the march, I wanted Bill to play the melody straight one time through, and then take it

out on the next pass—but yet still perfectly melodic in that perfectly Bill way—and then for the song to devolve and dissolve, with Shannon and Melvin dropping by the wayside. In other words to take the title of the song literally, and for it all to end with Bill’s solo guitar voice and his delay. I was looking for what I call “asymmetrical equilibrium,” which is something I look for over and over in art. The little sketch for this arrangment was a “first thought / best thought” thing on piece of scratch paper.

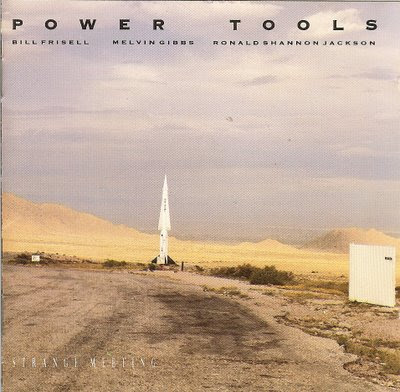

For the cover of the LP, I chose an image from Joel Sternfeld’s book,

American Prospects, which would come out the same year as the record. (That book was/is in the tradition of Walker Evans

American Photographs of 1938 and Robert Frank’s

The Americans of 1958, and I was hoping to emphasize both the Americanness and the

landscape quality of the music.) The album cover picture itself was taken seven years prior to the recording and is titled, “Roadside Rest Area, White Sands, New Mexico, September 1980.” It features the body of an old missile; a sign on corrugated fence saying “WOMEN” leading to a ladies’ room; and a view beyond of the White Sands Missile Range, a U.S. Government weapons-testing area for many years. It just seemed, with the title of the record, the music, these three guys,

right…although I’d be hard-pressed to explain why. I knew Sternfeld a bit by then and he graciously gave us the image for free, or for some nominal sum.

The band went on to do one fairly brief European tour in 1988. I’d hoped to come along, and perhaps even record more, but could not make it due to my own work schedule as a freelance journalist. I had a story deadline—I can’t remember for what. I heard some real positive feedback about the tour, and have a VHS tape of four songs from one performance in Cologne, Germany: “Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” “Unchained Melody,” When We Go” and “Wadmalaw Island.” These last two pieces are available via youtube and I think the other two will surface in the fullness of time.

Time goes by, so slowly, and time can do so much.

It’s a sad state of affairs that Island let the LP, and then the compact disc, go out of print. I called the label once to see what I could do about it and got the Kafkaesque run-around. I have no financial interest in the record (typical for my projects) but this put me in a particularly powerless position in terms of prying the thing free. Maybe I could / should re-visit the subject. The analog record sure sounds politely ferocious.

It’s also not just a little bit sad that there was no follow-up record nor no life as a band after that first tour. Bill had his own trio to feed and grow at the time (the wonderful one with Joey Baron and Kermit Driscoll if I’m remembering the timing correctly) and Shannon was increasingly drawn into a different orbit. What can I say? I’ll say it’s a shame that Melvin, Shannon and Bill did not play together again. They could have made beautiful music together.