Showing posts with label Steve Smith. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Steve Smith. Show all posts

Monday, June 10, 2013

Recently, again

*Black Sabbath review at Pitchfork. It's been a bumpy ride, but the new Sabbath album is finally here. I'm thankful that I had the space to muse on it at length. I'll echo Stereogum's Michael Nelson, who graciously shouted out my piece in his write-up of the new "God Is Dead?" video, and point out that the discourse surrounding this record has been especially lively. I disagree with Ben Ratliff and Adrien Begrand's evaluations, but they both make solid, compelling points—Ratliff re:, e.g., the oft-overlooked "insane party" aspect of Sabbath 1.0; Begrand re:, e.g., the tough-to-beat sturdiness of Iommi and Butler's last go-round with Ronnie James Dio under the Heaven and Hell moniker.

For a true expert opinion, I highly recommend Steve Smith's NYT Popcast discussion with Ratliff. I doubt there are many commentators covering 13 who have a more detailed working knowledge of Sabbath's entire history than Steve; I'd like to offer a special note of thanks to Steve for abetting my own last-minute crash course re: Sabbath's shadowy non-Ozzy, non-Dio years. I'm still immersed in those seven LPs, trying to make sense of the weird, divergent sprawl. For starters, I'm beginning to feel like Born Again and Headless Cross are both real keepers.

P.S. Phil Freeman's review went live after I published the round-up above, but that's well worth a look too. Again, I'm not on board with every one of his points—e.g., while I do hear Brad Wilk deliberately playing it safe, I (thankfully) don't think there's oppressive ProTools looping/"gridding" going on here; you can hear the patterns/fills fluctuating throughout the songs, in ways that you wouldn't if all the drum tracks on 13 were subject to a ruthless, industry-standard cut-and-paste job—but this is a very sharp evaluation with a provocative conclusion.

*Milford Graves preview at Time Out New York. I've had Milford on the brain lately, largely due to call it art. The lineup for Wednesday's Lifetime Achievement showcase—opening night of Vision Festival 18—is insane; I can't wait.

*Black Flag preview at Time Out New York. As Ben Ratliff has eloquently noted, in another thinkpiece/Popcast combo, the current bifurcated reunion is insane. When I interviewed Greg Ginn last July, he was playing to near-empty rooms with his Royal We project, which I caught twice (once at Iridium, of all places) over the course of a week. The situation is somewhat different now. I look forward to seeing how it all goes down.

Thursday, July 19, 2012

Flushing the pipes: Channel Orange and the art of speed-reviewing

Here, via Time Out New York, is my review of Frank Ocean's Channel Orange.

This version of the piece, the same one that appears in the current print issue of TONY, is actually my second stab at an assessment of Channel Orange, and the one I'm much happier with. At the end of the review linked above, you'll find a link to the first review I published, which went live the day of the album's surprise-attack midnight release.

The short answer to "Why are there two?" is that soon after I published the first one online, I realized that it had been a rush job. I spent more time with the album over the next couple days, and it steadily grew on me. I realized I could still complete a new version of the piece in time for our print deadline, and thanks to my patient and understanding editor, Steve Smith, take 2 is the one that ended up running.

This sequence of events sounds pretty straightforward, but the fact is that it kind of drove me insane last week. (My wife could certainly describe this state of mind in greater detail.) My initial response to the record—the follow-up, I should add, to my favorite album of 2011—was mixed, and as the rave reviews started rolling in, I started to second guess myself, not because I felt like my take needed to mirror everyone else's, but because I realized that I simply hadn't spent sufficient time with the record.

During my career, I've had to write surprisingly few rush reviews. Typically if I'm reviewing a record, I have the music weeks or months in advance. With the Ocean, though, that wasn't an option. I heard it for the first time when everyone else did, last Tuesday morning. As soon as the reviews started going live—i.e., pretty much immediately—I felt compelled to jump into the fray. I was talking about the album with some friends and fellow music writers over e-mail, but that didn't suffice; I felt, for no reason other that that journalists in the internet age tend to feel that they're late on a story (even something as in-the-grand-scheme-of-things trivial as a review of a newly released work of art) mere hours after the window on said story has opened, that I needed to publish immediately.

The problem with that urgency is an obvious one: First impressions are iffy. (I should state another obvious point here, i.e., that there's no such thing as a "correct" record review, only one where the writer has had sufficient time and space to get familiar with the album in question and work out their formal impression of it—the argument they want to make.) This is a constant pitfall of deadline-oriented writing-about-music (or writing-about-art, period) and this particular instance certainly wasn't the first time I'd published a review and second-guessed it. What was special in this case, was the intensity of my bummed-out-ness re: that second-guessing: not exactly the feeling that I had let the artist down (because, let's be serious, my Channel Orange review was one of approximately a zillion that have been published; in the end, what I said matters to relatively few people aside from myself), but the feeling that I hadn't given myself the time and space I needed to simply do a good job on the piece, to come up with something I could stand by and be happy with going forward. The latter criteria, incidentally, do apply to the second version of the review, the more positive one you'll find at the link above.

Along with the aforementioned bummed-out-ness came a painfully complete understanding of why I felt that way, and what I needed to do in the future to avoid feeling that way again. Film reviewers may very well have to settle for one pass through the movie in question, simply because of the logistical impracticality/impossibility of watching the entire thing again in time for their deadline. But music reviewers tend to have the luxury of at least a couple spins, and here's the reason why we ought to take full advantage of that luxury (or at the very least, why I plan to in the future): When you're hearing a record for the first time, especially a record that you've looked forward to, by an artist you already know you care about, you're not really hearing the record. You're hearing some kind of composite sonic image: the record you hoped you'd hear, overlaid on the actual thing. In many cases, and I think in the case of my Channel Orange experience, your expectations are so extensive and so powerful that they simply drown out the sounds that come out of the speakers. Listen a few more times, and you can begin to edge that essentially meaningless set of expectations out of the picture; you can, in other words, hear the record on its own terms rather than on yours. Now again, I'm not saying that at that point, whatever you write is somehow "correct." What I'm saying is that at least you're engaging with the given record in a fair way; you're giving it ample chance to reveal itself.

Record reviewing is no exact science. There may, in fact, be few more inexact sciences. But as I said above, it really comes down to the writer's own feelings. If others get something out of the piece, that's all the better, but as a writer, you simply want to be able to stand by what you wrote, to feel afterward that it accurately expresses, in an objective way, how you feel, what you'd meant to say. As any writer could tell you, sometimes that isn't the case, for a variety of reasons. Sometimes you finish a draft of a piece and it appalls you. If you're on deadline, you might hand it in anyway, because you have no choice, but you don't feel a sense of proud ownership. And that sense of proud ownership is all I mean to ponder here, i.e., how best to end up feeling that way. In the super-specific case of a record review, I think it's important to take one's time, or to take as much time as one has, because you're more likely to end up proud of what you've written, or at the very least to feel comfortable standing by it. Now, of course, there are plenty of records that have taken me far more than a few spins to warm up to—several years' worth of spins, in some cases—but I'm speaking here about a deadline-oriented situation. What you want to do in these cases is make sure you've flushed the pipes—that is to say, eroded as much of your essentially irrelevant and potentially insidious expectations as possible—before you drink the water. That's when you're doing your job, i.e., writing about the thing in front of you, rather than the version of the thing you've been carrying around in your mind. I was fortunate enough to get a second crack at Channel Orange; I hope that next time, I'll have the good sense to wait before taking my initial swing.

Labels:

channel orange,

frank ocean,

review,

Steve Smith,

Time Out New York

Monday, April 18, 2011

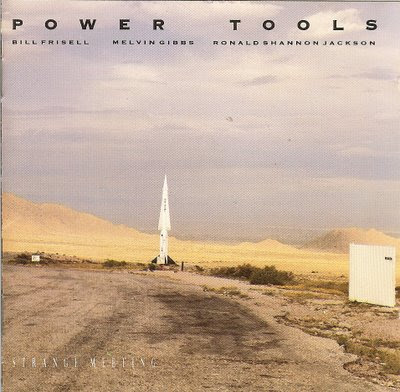

Power Tools/Strange Meeting: The Michael Mann jazz [now with producer's commentary]

UPDATE, 5.8.2011: A few days after posting this appreciation of Strange Meeting, I received a nice e-mail from David Breskin, who produced the record. He also contacted Steve Smith and he very kindly offered to a) fill us in on the details of this session, and b) correct one longstanding misconception, namely that—as mentioned below—Strange Meeting was originally intended as a quartet date with Julius Hemphill. Not true at all, it turns out!

Breskin followed up a few days later with a fascinating account of the making of the record. As you'll read below, there was nothing accidental about it; Strange Meeting was a true old-school PRODUCTION, complete with rehearsal, strategic preplanning and a real aesthetic backbone. (My sense is that there aren't a whole lot of jazz records being made this way anymore.) Breskin's text doubles as a fascinating insider's perspective on the NYC jazz scene in the ’80s. It's essential reading for any fan of that period, of Strange Meeting in particular, of the musicians involved in general, or for anyone interested in the way a producer can act as a true collaborator, setting parameters that liberate rather than constrict, ultimately yielding an ALBUM rather than just a collection of performances. Breskin's text, edited and fully approved by him, appears below my post.

"I thought Shannon’s playing might do something interesting to Bill and that Bill’s playing might do something interesting to Shannon, and that Melvin would be a perfect fulcrum and shifting counterweight: suitably fierce but appropriately subtle and supportive when need be and no road hog he. Anyway, that was my hope. I thought this could be a cool band, and Shannon always used to say, 'Nothing beats a failure but a try.' So, why not?"

—David Breskin on Strange Meeting

/////

I wrote a little while back about the idea that free jazz ought to be documented in the studio as well as onstage. Been thinking again about that the past few days, while immersing myself in Strange Meeting (Antilles), the lone officially released recording by Power Tools, the trio of Bill Frisell, Melvin Gibbs and Ronald Shannon Jackson.

I have heard from Steve Smith (who, as you can read here—scroll down to the 1987 section—regards Strange Meeting as a desert island disc and a perfect record) and other sources that this January, 1987 record date was originally scheduled to be led by Julius Hemphill. He didn't show, though—apparently due to illness—and a new scheme was quickly hatched. I'm not sure if the date was supposed to be these three gentlemen *plus* Hemphill or if one of them was called in to replace him, but at any rate, what you have here is the only in-studio meeting of Frisell, Gibbs and Jackson, and it is indeed a strange one. [NOTE: Hemphill was never a part of this date. Please see intro and addendum to this post for details.]

And really the strangest thing about it, given the aforementioned haphazardness of its organization, is how incredibly *together* it all sounds. You might expect some sort of free blowout: "Ah, fuck it—let's just improvise and roll tape." That is not what this record is at all, though. It is an honest-to-goodness full-length LP, paced as intelligently as any rock classic you could name.

You would honestly think this lineup had been together for years. All of the members contribute pieces, and the writing is more or less evenly split: three pieces by Frisell, three by Gibbs, two by Jackson, one collective jam and one cover (yes, "Unchained Melody"). This, to me, is the formula for success in jazz, and maybe even rock too, though it's much rarer. (Descendents/ALL comes to mind; their albums have always been everyone-pulls-their-weight-both-compositionally-and-instrumentally affairs.)

I'm skirting around the music itself, maybe because it's such an enigma. You can't typify what this band sounds like—you have to hear the whole record, really. Gibbs's compsitions, "Wadmalaw Island" and "Howard Beach Memoirs," just floor me. The former is a beautiful, alien quasi-ballad, held together by a Latin-ish vamp. Frisell's sublimely ’80s-ish reverb is just the right thing for it. The band sort of slinks along, doling out its energy gradually. You may never have heard Shannon Jackson play this sensitively. It's like undersea Miami Vice jazz from Pluto. And then Frisell brings out the distortion, and the poetry becomes a bit scary, almost Sharrockian. You think of synthesized seagulls, like in Don Henley's "Boys of Summer." This, to me, is the true ’80s jazz. Lush, sorta-dated-but-you-don't-care sonics mingling with heartbreak. But the real-time improvisation is right there—it's not frosted over with stiff arrangements or soupy sound.

The trio does hectic scribble just as well as it does noirish emoting. Jackson's "A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing" features a tumbling, brief, Ornette-ish head that gives way to a magical kind of clunked-out funk that only Shannon could provide. I would venture to say that his drumming is better here than it ever was in Last Exit. In that band, Shannon tends to go for the broadest gesture, either the martial, about-to-blow ramp-up or the boneheaded electric-blues beat. Here, though, he's actually playing free jazz, more or less, while also keeping the beat. Gibbs's chords jut out crudely, Frisell screams one minute, whispers the next (I tend to hate overly pedal-effected guitar, but Frisell uses pedals like a true surrealist on this record) and Jackson tumbles and exclaims. The beat is somewhere there, but it's not explicit. The band heads out the cargo hatch into space but they hold onto the line. What astounds me is that the piece is only three and a half minutes, but you get a real without-a-net free-jazz feeling in between the bookends of the heads, which themselves give off a very authentic, four-handcuffed-men-being-jostled-violently-around-a-room Ornette-head vibe. It's a true fusion of pop production practices—get in and get out quick—and free-jazz abandon. Great taste and less filling.

And this is what I mean about free-jazz sometimes jelling really well in the studio. Sometimes you don't want to hear a 30-minute live blowout. Sometimes you want to hear the chaos tastefully integrated, in a context you want to play and re-play. Sometimes limits are good.

There's so much else to love on Strange Meeting. I honestly don't know if there's a weak track. I'm spinning the collectively improvised track, "The President's Nap," right now, and as with a lot of Power Tools material, it sounds like the subtler cousin of Last Exit, not as balls-out aggressive but probably more fulfilling on a purely interactive level. Shannon starts out with one of those jaunty, Last Exity marches, Gibbs hops on the train, and Frisell tosses out waves of pure sci-fi sound. Then the whole thing tilts toward something scary and nuclear-sounding, like a parched landscape about to blow. The band is moving all at once, like a miasma in the sky, some sort of hot, creeping menace. The climaxes are hectic and—thanks in part to the outstanding recording quality—vibrantly detailed. It's not just free sound, not just noise. It's deep-listening abstraction, swirling together funk and rock and free jazz and technology and Michael Mann–ish ’80s humidity. You hear this and you feel almost embarrassed for anyone who was still chowing down on old-school, meat-and-potatoes acoustic free jazz circa ’87. This is a music of its time, the best kind in fact. There's a certain mist of cheese swirling around Strange Meeting, but the playing is so goddamn wholesome, so real and right on, that it just becomes part of the joy. It's an if-this-is-wrong-I-don't-want-to-be-right type of thing.

I could go on and on. Frisell's "Unscientific Americans" is another sci-fi Ornette-style tumble. I don't know Prime Time too well, but honestly this band sounds like what I'd *want* Prime Time to sound like, a true electrifying of the skittery, headlong O.C. vibe with none of those bummer boxy funk rhythms. Frisell is basically playing the laser gun here. The song is all the gnarlier, all the more "fuck you" because it's three minutes long. I've been spinning Strange Meeting all weekend, but I find myself appreciating it even more right now. I can't emphasize this pop/free-jazz vibe enough. It's like a not only benevolent but actually mutually beneficial ’80s-izing of avant-garde jazz. It's concise but it's not tidy. Sure it might be cool to hear this band stretch out for 40 minutes or so, but they want to play *songs*, start from coherence and then explode the universe in the time it would take to run down a bebop tune.

I wish I could stream Gibbs's "Howard Beach Memoirs" for you above. It's a parched, steely line, with so much internal poetry and narrative contour. I think of a (nonexistent) Michael Mann cowboy film, Dylan Carlson from Earth playing with a rhythm section that shifts like magma under his feet rather than plods. Frisell lets the alien spiders in after the head. Into the tech-jazz vortex. I think of those old, big, clunky, white-rimmed VHS tape boxes that snapped shut. Instead of snuffing the jazz out like some pillowy ’80s production can, the *casing* of this music, its presentation and milieu and delivery system, is friendly to the aesthetic. Shannon Jackson solos at the end of "Howard Beach," punching holes in the sky with his close-miked arena-rock toms.

And there at the end of it all is "Unchained Melody," romantic and wired all at once. Did the producer suggest it? Who knows, and who cares? You can in fact make a *record* of this music. You can trim it at the edges and not cut out what makes it tick. That way, you can listen again and again.

/////

*Sadly Strange Meeting does not appear to be available for legal download. You can, however, order a pricey autographed (!) copy direct from Ronald Shannon Jackson via his website. (There are a few Power Tools boots there as well, in addition to a bunch of intriguing Decoding Society selections.)

*Here's a nice clip of Power Tools playing Frisell's "When We Go." Check out this comment someone left: "Ronald Shannon Jackson and Bill Frisell are about a millisecond from obliterating into sun particles; some of the most visceral playing with refrain and control. Fortunately, Melvin's got the weight of the world within his thumb alone to keep the gamma rays from shooting skyward..." Nice.

*Here's Destination: Out on Strange Meeting back in ’08, featuring helpful context re: "Howard Beach Memoirs."

*Strange Meeting begs the question: What are other great fruitfully ’80s-ized (i.e., not just made in the ’80s but true products of the ’80s) avant-jazz studio recordings, albums on which the then-modern production style or record-making philosophy enhanced rather than dulled the impact of the music?

*Also: I don't know the Frisell, Gibbs or Decoding Society discographies all that well. Are there other records by any of these entities that get at the Strange Meeting vibe, or is this record really as anomalous and gemlike as it seems to be?

*Also, what do people know about the Antilles label? Of the catalog listed here, I only know the Air and Braxton records, but I'm very intrigued. What's up with that White Noise record (which features Paul Lytton)?

/////

A Few Notes on Power Tools and Strange Meeting by David Breskin

5.6.2011

I met Shannon Jackson in the summer of 1979, when I was an intern at The Village Voice. I conned Bob Christgau into letting me write some Riffs—it was hardly part of my job—but I wrote on Terje Rypdal, Bootsy Collins, Oregon and Weather Report, if memory serves. (That may be the first time Terje and Bootsy have ever been found in the same sentence, and if so, this would mark the second.) In any event, I met Shannon after one of his gigs at the Public Theater that summer—he was playing with Blood Ulmer, David Murray and I think Amin Ali was the bassist. And I went back to Providence for my senior year in college and also my last year as jazz director of WBRU (under the name “Spottswood Erving”) and Shannon and I stayed in touch in epistolary fashion, and developed a strong connection.

After college I moved to New York City in the fall of 1980 and ended up producing The Decoding Society’s Mandance and Barbeque Dog, as well as Shannon’s own “solo” drum record, Pulse, bringing along my poetic mentor from college, Michael S. Harper, to collaborate with Shannon on a few tracks. In the fall of 1981, I went on a long European tour with the band and got to know everyone pretty well, including, of course, Melvin Rufus Gibbs and Vernon Reid. I also met Bill Frisell in the early ‘80s and was absolutely wowed by his playing: I thought he might be the “Thelonious Monk of the Guitar” or something like that. I got to know Bill, grew fond of him, and in due course produced a collision between him and Vernon, Smash and Scatteration, recorded in the winter of 1984 and released in ’85. My internal code for that project was: “Mr. Rogers Meets The Wild Child” though originally that record was intended to be for a trio, with John Scofield being the third guitarist. We just couldn’t make the schedules work.

Over those years, I’d brought Bill to some Decoding Society gigs and brought Shannon to come see Bill play. They were full of mutual admiration. As different as their own music was, they are both, in a sense, country, and there was an easy camaraderie and feeling at the start. I remember Shannon saying, upon seeing Bill play for the first time, “Look here! There’s nobody, there’s nobody that plays a melody like that.” Of course, Bill had heard Shannon’s work with Cecil Taylor and with Ornette, and was really interested in what he was doing, and Bill also admired Melvin’s playing from the Decoding Society gigs and other downtown things.

I remember thinking: if Marx said he was trying to turn Hegel on his head, maybe I could turn the Jimi Hendrix Experience on its head. A very, very limited analogy, but hey, maybe the guitar player could be the pink guy and the rhythm section the darker-than-pink-guys. A powerfully inverted triangle. There was a real racial walling-off in the “avant” music community at that time—what was white, what was black, blah blah blah. I found it hateful then, and still find it so, though of course it makes perfect sense historically. Didn’t Ralph Ellison say he was an integrationist because an “integer” is a whole number? Well, I want to be in that number when the saints come marching. Anyway, that was a part of my thinking in making this project, but don’t get me wrong: it was not some kind of overdetermined racial thing—it was about the music. It’s just that I was cognizant of the larger context, and that some people would see it as somehow “strange” and that’s one reason for choosing Bill’s song as the title track, and the album cover art being what it is. Also strange, in a different sense, because Shannon’s music was so heavy (in weight) and Bill’s was so light, in the sense of ethereal and floaty. I thought this combination might create some heat-generating friction.

I came to the three of them with an idea of a cooperative trio, and making a record as a start. It was always conceived as a trio, a power trio. There was never a horn involved. I don’t know where this story about Julius Hemphill’s involvement came from—you know, that he was was sick and couldn’t make the date, and so an unplanned bare-bones trio recorded spur of the moment. That story is totally, uh, spurious. I’d met Julius at most twice: among other things, he and Michael Harper had collaborated; and for a moment there Bill toured with him in the same band as Nels Cline wouldn’t ya know it?; and Tim Berne, who I was in touch with, was close to him…so it’s not far-fetched. But there was no discussion of Julius being included. And frankly, after the rather horn-heavy Decoding Society, I specifically wanted this to be devoid of hornage, wanted it to be really open, very spacious, where the deer and the fucking antelope roam. I wanted there to be lots of room for Bill, and yet wanted this not to be one of those trio record where it feels like lead-voice-plus-rhythm-section. I just wanted to couple Bill to this deeply heavy rhythm section and see what kind of freight that train might pull. I thought Shannon’s playing might do something interesting to Bill and that Bill’s playing might do something interesting to Shannon, and that Melvin would be a perfect fulcrum and shifting counterweight: suitably fierce but appropriately subtle and supportive when need be and no road hog he. Anyway, that was my hope. I thought this could be a cool band, and Shannon always used to say, “Nothing beats a failure but a try.” So, why not?

We had one planning meeting about the date up at my apartment on 109th street, the four of us. I asked each of them to bring in three tunes. I asked them to bring in songs which would work for this group and to think of who’d be playing it, whether it was brand new material or something previously recorded. I’d heard some of Melvin’s writing in and around the Decoding Society, really liked it, and wanted him, compositionally, to be an equal partner to Shannon and Bill on the record, and not the less-famous sideman. I wanted 3 + 3 + 3 + 1 = 10 songs. Five songs a side, and song-length songs, not long jams. The last song (the +1) would be a cover, a great song but not played straight, something radically recontextualized. In the end, Shannon brought in two pieces, “Blame and Shame” and “Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing;” Bill brought in three, “When We Go” and the title track (both of which he’d released on Rambler in 1985) and the new “Unscientific Americans;” and Melvin brought in three, “Wadmalaw Island,” “A Song is Not Enough,” and “Howard Beach Memoirs.” The title of this last piece was a riff on the popular Neil Simon play (Brighton Beach Memoirs) which had opened on Broadway in 1983, running though 1986 and was made into a movie that year. Of course, the title and piece specifically refer to the Howard Beach hate-crime of December 1986, when three African-American youths were attacked by a gang of stupid young pink people in Queens. One of the victims ended up badly beaten and one ended up run-over by a car and killed while trying to escape.

If memory serves, the trio rehearsed in Shannon’s studio, I think twice, maybe thrice before the recording. I remember being at one or two of these rehearsals, because I made rehearsal notes to prepare for the recording—something I’ve always done when producing. Anyway, the point is that the project was organized and not “haphazard”: the thing was conceived, bantered about, thought out, rehearsed, and then recorded. For all we knew, this might become a real band and this was just the beginning.

For the date, I picked Radio City Studios, up there back behind the hall, in that historic building. I think I was first there watching John Zorn his “Spillane” piece in the summer of ‘86. Loved the sound of the room, the historic old-fashionedness of the place. Frisell was on that date, as well as Bobby Previte. (A zillion years later—well, fourteen—I’d re-connect with Bobby to produce his 23 Constellations of Joan Miro, but that’s another story.) Anyway, at the “Spillane” session I’d met the engineer Don Hunerberg, who I think was something like a house engineer for that room, and thought he was terrific. So when my normal wingman Ron Saint Germain was not available for Power Tools, we happily ran with Don. (Small footnote: I ended up back in the same room six months later, producing “Two-Lane Highway” for/with John Zorn, his “concerto” for Albert Collins, which also was on the Spillane record. I’d written a story on Collins for Musician magazine years before, turns out my cousin in Chicago booked him, and Melvin and Shannon also came in for that date with Zorn and Albert.) Back to Power Tools: I wanted the session to be live, and wanted no editing, no mixing, no overdubbing. It was what it was: like a primary document, like an “early” recording. I wanted the “pressure” of live performance. That band was about a certain kind of pressure….spatial pressure, temporal pressure, rhythmic pressure, tonal pressure, the pressure of personalities and personal history. I knew we could go for multiple takes of every piece, and just settle arguments that way.

Regarding the group piece: “The President’s Nap.” It happened like this: Shannon was in the studio, warming up, playing by himself, with Melvin and Bill in the room getting ready. I liked what Shannon was playing and told Don to “roll tape” though we were beginning to roll early brutal digital two-track bits, even if tape was what we had in our minds. And I just gestured to Melvin and then Bill to start playing, and they did. The piece developed a beginning, a middle, and an end, just naturally. Game, set, match. It was a free improvisation, completely unplanned and obviously untitled. I offered “The President’s Nap” as a title, given that it’d recently come out in the press—sometime in Reagan’s second term—that the President liked to take a daily afternoon journey to dreamland. Given what Reagan did while awake, perhaps this was not so harmful. The title cracked everybody up, because obviously it spins the music in a slightly comically noirish if not horrifying direction, and it stuck. (Bill’s “Unscientific Americans” was also untitled as of the session, and I suggested that title after the Roz Chast 1986 book of cartoons of the same name. Bill is something of an amateur cartoonist in his own right, and is Roz Chastian himself, it might be fairly said.)

Regarding “Unchained Melody”: yeah, not to sound Monty Pythonish about it, but that was my idea, eagerly seconded by Shannon. I didn’t want to cover a song that was part of the jazz canon and that had been covered extensively by contemporary jazz artists, or even those in our immediate past. And I was also looking for a song that I thought Bill could really just rip into, and undo. Here was a song that had been covered a gazillion times, but you know, Alex North wasn’t in the Ella Songbooks and wasn’t of any interest to Wynton and his crowd, and it wasn’t like covering yet another Monk or Wayne tune. It was a pop song (though Al Hibbler did it way back!) recorded first as a theme for a mid-‘50s prison movie, Unchained, hence the “Unchained” in the title. Of course it’s famously a love song, but I was also thinking more abstractly of the Hy Zaret lyric “and time goes by, so slowly / and time can do so much.” Ain’t it true, Shannon, Melvin and Bill? Well, you don’t have to be a musicologist to see how that sentiment might play into this record and this band. Shannon’s point of reference was the Righteous Brothers’ version. For me, it was the Willie Nelson version on his classic Booker T. Jones-produced Stardust record from 1978. I’d gone out on the road with Willie (I think in 1982) for a Musician piece, and really came to love his way with standards, and of course Shannon is as Texas as it gets, and I played Willie’s recording for him, which knocked him out. (Willie then led me to Miles Davis, and later to We Are The World—everything overlaps with everything else—but those are other stories.) Extra-elliptical aside: “Righteous Brothers” became my inside code back-up name for this band, if “Power Tools” couldn’t be used, but that would have been pretty darn “meta” at the time and I can imagine what the legal bills might have been like. Again, this would have gone against the racial stereotyping in about three ways.

Anyway, I am very much a non-musician—I pretty much don’t know anything about music from a technical standpoint—but occasionally I have an architectural or arranging idea and “Unchained Melody” was such a case. I wanted Shannon to open with solo voice, and to play the song as a march. Always loved Shannon’s way with marches and martial beats and guessed that in hundreds of covers “Unchained Melody” had never been played as a march. (And this was before the U2 cover and the Cyndi Lauper cover and before the song was widely and wildly re-popularized by the movie Ghost, which didn’t come til 1990. In 1987, “Unchained Melody” was like a great deserted town, you know a place that had been a boomtown in the ‘50s but there wasn’t anybody living there anymore: The Last Picture Show.) And after establishing the march, I wanted Bill to play the melody straight one time through, and then take it out on the next pass—but yet still perfectly melodic in that perfectly Bill way—and then for the song to devolve and dissolve, with Shannon and Melvin dropping by the wayside. In other words to take the title of the song literally, and for it all to end with Bill’s solo guitar voice and his delay. I was looking for what I call “asymmetrical equilibrium,” which is something I look for over and over in art. The little sketch for this arrangment was a “first thought / best thought” thing on piece of scratch paper.

For the cover of the LP, I chose an image from Joel Sternfeld’s book, American Prospects, which would come out the same year as the record. (That book was/is in the tradition of Walker Evans American Photographs of 1938 and Robert Frank’s The Americans of 1958, and I was hoping to emphasize both the Americanness and the landscape quality of the music.) The album cover picture itself was taken seven years prior to the recording and is titled, “Roadside Rest Area, White Sands, New Mexico, September 1980.” It features the body of an old missile; a sign on corrugated fence saying “WOMEN” leading to a ladies’ room; and a view beyond of the White Sands Missile Range, a U.S. Government weapons-testing area for many years. It just seemed, with the title of the record, the music, these three guys, right…although I’d be hard-pressed to explain why. I knew Sternfeld a bit by then and he graciously gave us the image for free, or for some nominal sum.

The band went on to do one fairly brief European tour in 1988. I’d hoped to come along, and perhaps even record more, but could not make it due to my own work schedule as a freelance journalist. I had a story deadline—I can’t remember for what. I heard some real positive feedback about the tour, and have a VHS tape of four songs from one performance in Cologne, Germany: “Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” “Unchained Melody,” When We Go” and “Wadmalaw Island.” These last two pieces are available via youtube and I think the other two will surface in the fullness of time. Time goes by, so slowly, and time can do so much.

It’s a sad state of affairs that Island let the LP, and then the compact disc, go out of print. I called the label once to see what I could do about it and got the Kafkaesque run-around. I have no financial interest in the record (typical for my projects) but this put me in a particularly powerless position in terms of prying the thing free. Maybe I could / should re-visit the subject. The analog record sure sounds politely ferocious.

It’s also not just a little bit sad that there was no follow-up record nor no life as a band after that first tour. Bill had his own trio to feed and grow at the time (the wonderful one with Joey Baron and Kermit Driscoll if I’m remembering the timing correctly) and Shannon was increasingly drawn into a different orbit. What can I say? I’ll say it’s a shame that Melvin, Shannon and Bill did not play together again. They could have made beautiful music together.

Saturday, January 08, 2011

I am not a jazz journalist

[UPDATE: This post has elicited a number of insightful responses, some of which you'll find in the comments below. Howard Mandel has shared his thoughts on his own blog.]

/////

I'm just returning from a Jazz Journalists Association town hall meeting—"What is the state of jazz journalism now and what are its future prospects?"—held to coincide with APAP and NEA goings-on about town, as well as with Winter Jazzfest, which I attended last night and which I'm enthusiastically headed back to in a few hours. For a number of reason, mainly my own over-politeness, I failed to get a word in at the gathering, and I left feeling frustrated by that fact. I had a few things to say, and so I'll say them here.

The question at hand in this meeting was, as I gathered it, "How do we survive as jazz journalists?" The laments being aired were familiar ones: Print outlets are drying up, and even as online outlets are proliferating, online outlets that pay well are scarce. In one sense, I felt a bit distant from this conversation due to the fact that I have a staff job writing about music at Time Out New York. For this, I am infinitely thankful—it affords me a highly visible platform, as well as a good deal of freedom to express myself elsewhere as I see fit.

But I also felt distant from this conversation in another, more important sense. When I interviewed Anthony Braxton a few years back, he said to me emphatically: "I am not a jazz musician, and please put that in your article." Though I have a great deal of respect for my colleagues in the JJA—such as Howard Mandel, David Adler, and Laurence Donohue-Greene and Andrey Henkin of All About Jazz—and I'm proud to be a card-carrying member, I feel like I need to make a similar stipulation in terms of my own work as a writer, and more broadly, as a lover of music: I am not a jazz journalist.

It's absolutely true that I love jazz and—as any reader of this blog, or for that matter my fiancée, will tell you—and spend an inordinate amount of time listening to it, analyzing it, hearing it live and just generally obsessing about it. BUT all this activity does not occur in a vacuum. As I took great pains to stress in this 2006 post, one of the very first things I ever wrote on this blog, I experience music in a countless ways: listening to the radio while driving, singing karaoke, dancing at the weddings of friends and families, writing and performing with my band STATS, listening to promo downloads at the office or to my iPod on the train. By the same token, my tastes are wide open. In other words, I love jazz, but I am in no way wedded to it as a listener or as a writer, and though I realize that my position is unique and privileged, I'd state with caution that anyone who is wedded to Jazz Journalism—i.e., rather than, say, Music Journalism (or even Cultural Criticism or even something way broader)—per se as a profession may have a difficult road ahead.

David Adler acknowledged this in the meeting by indicating that he was probably less familiar with mainstream pop than he ought to be. The mention of Justin Bieber elicited quite a few snide smiles. But the plain fact of the matter is, a fact that ought to be acknowledged by anyone who's being paid to think about music, there's a lot of REALLY GREAT STUFF going on in mainstream pop these days. I don't need to bore anyone with some paean to My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, but I think it needs to be stated that we writers-about-music who love jazz shouldn't make it our beeswax to learn about pop because it might make us more marketable, we should do so because if we don't, we're cutting ourselves off from some really wonderful and fascinating music.

This is a lesson I've learned gradually. I've been a music snob my whole life, prattling on and on about esoterica, and when it comes down to it, some of my favorite music ever made is music that very few people have ever heard of. But over time, I began to realize that obscurity was not in any way a sign of quality. I came at music backwards, learning about DIY rock and metal first and then catching up re: all the classics. It was only a few years ago that I finally realized what every drive-time commuter has understood for decades: that Led Zeppelin is considered one of the greatest bands of all time because they FUCKING RULE, not because they play to some bullshit lowest common denominator. I'm not saying that all pop is great, but I am saying that to willfully insulate yourself from popular music, or from ANY music is to cut off a crucial air supply, not just regarding your career but regarding your enrichment as a lover of art.

When I first got to Time Out New York, I came carting a portfolio of pieces on jazz artists, pieces on experimental artists, all kinds of super esoteric stuff. I held these up as a badge of honor: "Look at how exclusive and rarefied my knowledge is," etc. And I'm still very proud of those pieces, as well as all the pieces I've written for Time Out on little-known artists ranging from avant-jazz pianist Burton Greene to death-metal visionary Steeve Hurdle. But you know what? I'm just as proud of my pieces on Francis and the Lights, and Chris Brown and Nicki Minaj. Having the opportunity to sit down with the latter for an interview was one of the most enjoyable and stimulating things I did in all of 2010. Taking on that assignment wasn't some sort of concession or compromise: What it was, was straight-up enlightening.

And our best writers-about-music show us this on a weekly basis. Think of Ben Ratliff, who can inspire you take a second look at either the doom-metal band Salome or soul-jazz great Dr. Lonnie Smith; or Nate Chinen, who can do the same for Josh Groban, Marnie Stern or the Tristano-ite Ted Brown. Or my TONY colleague Steve Smith, who could school you on Nas, King Crimson, Henry Threadgill, Edgard Varèse or a million others as the situation demands. Or Phil Freeman, who can—and frequently does—start provocative discussions on anything from Borbetomagus to Iron Maiden to Miles.

And that latter name (Miles) is an important one. Now it's fashionable to turn up our noses at the out-of-it critics who dissed Miles's electric experiments. With the benefit of hindsight we can see that he had just outgrown the tidy genre tag of "jazz" and needed to grow, right? But by emphasizing our jazz-journalists-ness over our lover-of-music-ness, maybe we're just echoing those critics' narrow-minded approach. If we expect broad-mindedness, resolute outside-the-boxness from our greatest and most widely influential artists (our Miles-es and our Beefhearts and our Kanyes), we need to expect the same of ourselves as thinkers-about-music.

BUT let me say, that I'm not advocating for some nebulous nonspecialization, some completely level playing field wherein we insist of ourselves that we GIVE EVERYTHING A CHANCE, do or die. No, that would lead to a world of spread-way-too-thin dilettantes. What I'm saying is that we need to foster a non-monogamous approach to the idea of specialty. Every writer-about-music worth anything has certain areas of affinity, a handful (finite yes, but always expandable) of styles or areas that make their heart flutter with excitement. And by the same token, every one of those writers, has massive blind spots—stuff that they don't know a damn thing about. What I'm saying is, let's celebrate the multiplicity of the former, let them play off of and inform one another. (In my personal pantheon, jazz mingles with metal, with classic rock, with punk, with pop, with hip-hop and more.) And let's also say, in certain cases, "You know what? I really don't know anything about MUSICAL STYLE X, and at least for today, I'm okay with that." Let's follow our innate tastes and distastes, in other words, without walling ourselves off.

Again, I'm not saying, "Don't specialize." I'm just saying, "Let a little air in." Our best outlets for music coverage are the ones that allow you to glimpse the world beyond their particular area of focus. A Blog Supreme, which alludes frequently to the indie-rock sphere; Destination Out, which makes a constant effort to portray avant-garde jazz as vital and inviting rather than some pallid curio. And stretching further out, Burning Ambulance and Signal to Noise, which celebrate the esoteric spirit while still maintaining their authoratativeness, and Invisible Oranges, which cheerleads for the metal underground while at the same time calling B.S. on the scene's inherent hypocrisies.

All I'm really saying here is: Let's not pigeonhole ourselves right out of the gate. Let's bond over our shared love of this music without building a fence to keep non-jazz-obsessives out, and to blind us to the possibilities of the pop world and beyond. The best jazz I heard in 2010—records by the Bad Plus, Chris Lightcap, Dan Weiss and others—didn't need some sort of rubber-stamp Seal of Jazz Approval to convey its message. It just sounded beautiful, in a way that didn't need to be explained. As I noted in my Bad Plus post, my fiancée, Laal, often helps me to open my mind re: how I think about the jazz I take in: The operative question isn't "Was that a great jazz show?," it's "Was that a great show?" Full stop.

All of the real movers on today's jazz scene know this well. Adam Schatz, say, or Darcy James Argue, or Ethan Iverson, all of whom have demonstrated their engagement with the world outside the jazz bubble in a number of shrewd ways. Aside from all the great music I heard at last night's Winter Jazzfest, one of the coolest encounters I had was with the saxist Darius Jones, a scary-good musician and an extremely nice guy whom I've known for a few years now. I shook his hand, congratulating him on what a fine set he'd played with Mike Pride's From Bacteria to Boys, but all he wanted to do was grill me about what it was like to interview the great Nicki Minaj. So again, all this great music exists on one plate for the artists—let it also be so for those of us who cover it.

Friday, January 08, 2010

Jack DeJohnette at Birdland, etc.

It's the first week of the new year, and it's a busy one, musicwise and otherwise. Coming off a solidly lengthy "winter break"--it felt a little like college again--filled with good people (for one: a dear old comrade, now living overseas, payed a visit with his girlfriend) and a healthy amount of doing-nothing time.

The coming weekend was supposed to be all about ALL. Sadly, the shows--which I had previewed in this week's TONY--have been cancelled, a fact I find mildly devastating. I really hope that whatever's ailing one of the greatest drummers alive abates soon. Fortunately the Winter Jazzfest lineup looks stellar.

/////

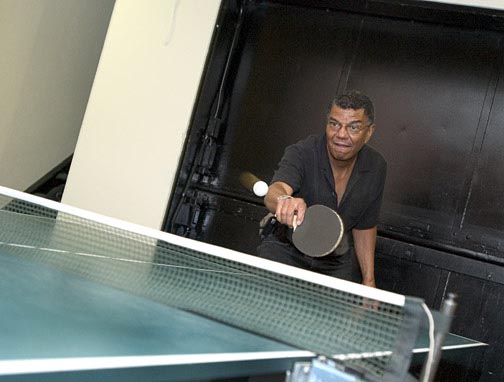

[Jack DeJohnette pic: courtesy Celebrities Playing Table Tennis (!)]

Re: Jazzfest, I warmed up with Jack DeJohnette & Co. at Birdland last night. (Thanks to Steve for the multiple Twitter tips [e.g.] on this gig--I didn't even realize it was going down.) A great set, and I encourage you to head down tonight or tomorrow, even if it means missing a bit of WJF. I'd never caught DeJohnette live before, and that was a major draw, but I think what really enticed me was the backing band: Rudresh Mahanthappa on sax, David Fiuczynski on guitar (double-necked!), George Colligan on keys (w/ some serious MIDI vibes, simulating harpsichord, harmonium, organ, etc.) and Jerome Harris on acoustic bass guitar. I wasn't disappointed.

During the first few minutes of the opening tune, "One for Eric"--a classic that debuted on the fantastic Special Edition album in 1979--I was struck by how turbulent the improvising was. Whenever I'm hearing challenging or abstract jazz in a club like Birdland, I can't help but feel for those tourist-types who may have wandered in unawares in search of smooth dinner music. I'll just say I was glad I wasn't dining last night. DeJohnette really smacks the drums, and on "One for Eric" he laid down a rocky, free-time landscape once the solos got going. (He saved the incredibly supple and intricate low-volume swing for the bass solo.)

But the cool thing about DeJohnette as a bandleader and composer is that he makes that kind of wildness feel accessible and fun. The set closer, "Ahmad the Terrible," with its knotty melody and carnival-esque acceleration, registered more like off-the-wall party music than anything foreboding. And even during the prickly unaccompanied Mahanthappa solo--surely the out-est moment of the evening--that preceded the tune, DeJohnette flashed a few grins at Harris, which took a little of the edge off.

The drummer really knows how to construct a set. Last night, in addition to the bookend classics mentioned above, we got "Music We Are," a killer ballad with DeJohnette rocking the melodica in fine, yearning style--weirdly, his sound on the instrument reminds me of the beautiful synth-harmonica theme that accompanies the underwater level on the classic Super Nintendo game Donkey Kong Country--and some chaotic rubato poetry, "Dearly Beloved"-style, from the ensemble. Then, "Spanish Seven," a fast Latin-y romp in said time signature that built into a nasty sort of fusion, part electric-Miles funk and part jaunty klezmer. (I remember Colligan riding the groove with unhinged glee.) And "Ahmad" concluded with an odd Indian-music breakdown, with Colligan providing faux-harmonium and Harris on otherworldly vocals, a little like the higher pitched Tuvan stuff demonstrated here.

So it was all pretty out there but also down to earth. Challenging, but without any stone-faced self-importance. Flashy and occasionally even a bit gimmicky in its eclecticism, but not watered down. You left feeling like you'd been in good, honest hands. And somewhat unexpectedly, with less recollection of the individual players than of the band as a single organism. Wouldn't wanna deny props to Mahanthappa's solos (nimble and peppery, with a lot of sublimated freakiness) or Fiuczynski's (effortlessly classy on the fretted guitar neck, sproingy and slightly alien-sounding on the fretless one), but DeJohnette's concept(s) prevailed, and it was one all the sidemen got behind wholeheartedly. I don't know DeJohnette's full discography well enough to tell you how unprecedented this group's sound is within his catalog--in a Voice blurb, Jim Macnie alludes to a 1989 album called Audio-Visualscapes that I haven't heard--but I really think someone should record this band.

The coming weekend was supposed to be all about ALL. Sadly, the shows--which I had previewed in this week's TONY--have been cancelled, a fact I find mildly devastating. I really hope that whatever's ailing one of the greatest drummers alive abates soon. Fortunately the Winter Jazzfest lineup looks stellar.

/////

[Jack DeJohnette pic: courtesy Celebrities Playing Table Tennis (!)]

Re: Jazzfest, I warmed up with Jack DeJohnette & Co. at Birdland last night. (Thanks to Steve for the multiple Twitter tips [e.g.] on this gig--I didn't even realize it was going down.) A great set, and I encourage you to head down tonight or tomorrow, even if it means missing a bit of WJF. I'd never caught DeJohnette live before, and that was a major draw, but I think what really enticed me was the backing band: Rudresh Mahanthappa on sax, David Fiuczynski on guitar (double-necked!), George Colligan on keys (w/ some serious MIDI vibes, simulating harpsichord, harmonium, organ, etc.) and Jerome Harris on acoustic bass guitar. I wasn't disappointed.

During the first few minutes of the opening tune, "One for Eric"--a classic that debuted on the fantastic Special Edition album in 1979--I was struck by how turbulent the improvising was. Whenever I'm hearing challenging or abstract jazz in a club like Birdland, I can't help but feel for those tourist-types who may have wandered in unawares in search of smooth dinner music. I'll just say I was glad I wasn't dining last night. DeJohnette really smacks the drums, and on "One for Eric" he laid down a rocky, free-time landscape once the solos got going. (He saved the incredibly supple and intricate low-volume swing for the bass solo.)

But the cool thing about DeJohnette as a bandleader and composer is that he makes that kind of wildness feel accessible and fun. The set closer, "Ahmad the Terrible," with its knotty melody and carnival-esque acceleration, registered more like off-the-wall party music than anything foreboding. And even during the prickly unaccompanied Mahanthappa solo--surely the out-est moment of the evening--that preceded the tune, DeJohnette flashed a few grins at Harris, which took a little of the edge off.

The drummer really knows how to construct a set. Last night, in addition to the bookend classics mentioned above, we got "Music We Are," a killer ballad with DeJohnette rocking the melodica in fine, yearning style--weirdly, his sound on the instrument reminds me of the beautiful synth-harmonica theme that accompanies the underwater level on the classic Super Nintendo game Donkey Kong Country--and some chaotic rubato poetry, "Dearly Beloved"-style, from the ensemble. Then, "Spanish Seven," a fast Latin-y romp in said time signature that built into a nasty sort of fusion, part electric-Miles funk and part jaunty klezmer. (I remember Colligan riding the groove with unhinged glee.) And "Ahmad" concluded with an odd Indian-music breakdown, with Colligan providing faux-harmonium and Harris on otherworldly vocals, a little like the higher pitched Tuvan stuff demonstrated here.

So it was all pretty out there but also down to earth. Challenging, but without any stone-faced self-importance. Flashy and occasionally even a bit gimmicky in its eclecticism, but not watered down. You left feeling like you'd been in good, honest hands. And somewhat unexpectedly, with less recollection of the individual players than of the band as a single organism. Wouldn't wanna deny props to Mahanthappa's solos (nimble and peppery, with a lot of sublimated freakiness) or Fiuczynski's (effortlessly classy on the fretted guitar neck, sproingy and slightly alien-sounding on the fretless one), but DeJohnette's concept(s) prevailed, and it was one all the sidemen got behind wholeheartedly. I don't know DeJohnette's full discography well enough to tell you how unprecedented this group's sound is within his catalog--in a Voice blurb, Jim Macnie alludes to a 1989 album called Audio-Visualscapes that I haven't heard--but I really think someone should record this band.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Melvins/Blue Notes/Parker/Taylor/MORE

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

MELVINS/BLUE NOTES

the new lineup of the Melvins proved itself a smashing success w/ the recently dropped "(A) Senile Animal," but they sealed the deal big time at Warsaw tonight. the show simply kicked total ass.

openers were weak to piss poor. i'm a huge fan of Joe Lally's bass playing in Fugazi, but his solo stuff doesn't do much for me--basically very chill songs built around bass vamps and Lally's speak-singing. the songs he sang on the last three Fugazi records were awesome, but these just feel half-baked. it was interesting to hear him backed by Dale Crover and Coady Willis of the 'Vins and (of all folks) Melvin Gibbs on "lead" bass, but the set was pretty much a snooze.

Ghostigital (i think one of the dudes from the Sugarcubes) just totally blew. boring arty dance music w/ rambling poetry over top.

then was Big Business who played a really solid set of mostly new stuff. this was the first time i heard them live where the mix was just right. their music is straightforward and relentless and, it must be said, very Melvins-like, but they've got a really strong identity, owing to what awesome players Jared and Coady both are. the notsosecret weapon is Jared's voice, a hugely powerful and melodic instrument. Dale joined in on guitar on a few tracks including "Easter Romantic" from "Head for the Shallow" ("White Pizzazz" was also played, after Dale exited), which i thought was probably the best heavy record of '05.

set segued right into the 'Vins set. the two drummers started up this intricate marchy-type vamp, which led into (i think i'm remembering this right) "The Talking Horse," the first track from the new record (which weirdly was the last track on the promo disc i got; entire record was reversed from actual track order and i'm not sure if that was a mistake or just the Melvins messing around). a good deal of "Animal" was played and the stuff simply sounded flawless (didn't hurt that Warsaw is an excellent room with near-perfect sound). usually the drummers would sort of jam out at the end of the songs and launch right into the next one. pacing and setlist were amazing; i heard songs i never expected to hear live, such as "Revolve," "Sky Pup," "Set Me Straight" and..."Oven," which is perhaps the heaviest song ever written and was like a moment of communion for me and my Stay Fucked bros--we opted to attend this show together instead of practicing--b/c we cover that song live. then there were the staples, such as "Let It All Be," "The Bloated Pope" (totally badass track from the very spotty "Pigs of the Roman Empire" record), "The Bit" (which sounded completely massive and benefited from a creepy drawn-out intro), "The Lovely Butterfly" and "Hooch."

it's true that there are certain songs that are in every Melvins set (no "Night Goat" tonight, though), but they play all the material with absolute conviction; they simply do not phone shit in. you might be wondering why i hadn't mentioned how the new lineup (Jared and Coady from Big Business are now in the band if that wasn't already clear) affects the sound and i think the reason is that the new guys fit in so seamlessly. the new songs already sound like classics and the old ones sound pretty much the same but with the added punch of an extra drummer. i really think this new record is one of the best of the band's career and this live show was a whole lot better than the other two i've seen. special props again to Jared's voice: check his performance on "A History of Bad Men" on the record and you'll see what i mean. like Buzz, he can be ferocious and melodic at the same time.

don't miss this band if they come back! hail Melvins! can't believe how long they've been around and how they keep kicking ass completely outside of the spotlight. who else even comes close to this kind of longevity and consistency let alone constant renewal. damn, these guys are just...

***

so i wanted to sort of revisit something from the last post. was trying to home in a certain period of jazz and i cast too wide a net. what i'm really talking about are the more avant-garde-leaning records on Blue Note from the early to mid '60s. i think this music is unparalleled in jazz--total virtuosity and control but with an experimental streak. but CONTROLLED, formal, TOGETHER. not free jazz. free jazz lives but it doesn't have the depth of this music. i'm talking about (partial list):

Andrew Hill - Point of Departure (3.21.64)

Andrew Hill - Andrew!!! (6.25.64)

Grachan Moncur III - Evolution (11.21.63--> day before Kennedy assassination! i

interviewed Grachan and he said he got chills listening to the funeral broadcast the next day because the horns playing taps reminded him of the dirgey title track of "Evolution" recorded one day prior.)

Jackie McLean - One Step Beyond (3.1.63)

Sam Rivers - Fuschia Swing Song (12.11.64--> one day prior to Tony Williams's 19th birthday)

Don Cherry - Complete Communion (12.24.65)

Eric Dolphy - Out to Lunch (2.25.64)

you'll notice that Tony Williams appears on many of these. i feel that he is the best jazz percussionist who ever lived, and one of the finest musicians period that i've ever been exposed to. he played music, not drums. utter finesse and conviction in every note. few things feel more sublime to me than the above-mentioned music and especially Tony's part in making it. this was such a special time.

uniformly strong WRITING on these discs. every piece hummable--never just heads. structural fascinations--Cherry's suite formats, Hill's episodic "Spectrum"--solos to melt your heart and brain (think of Jackie McLean on title track of "Evolution"). real improvisation and composition perfectly balanced. it's dumb that Blue Note lets these things waver in and out of print--as much as i love Coltrane and Miles and Duke and a ton of more well known things, these--and a bunch of related sessions from around the same time and with a lot of the same players--are really the essential records for me, my gold standard for jazz.

[a HUGE thanks needs to be given here to Andrew, Joe and Russell, dudes who first helped me cultivate my love of the aforementioned jazz regions and to Schaumann and Jeff, who understand exactly what i'm talking about when i gush about this vital realm of art.]

*****

Monday, October 16, 2006

COMPLETE COMMUNION / STEVE SMITH

Don Cherry's "Where Is Brooklyn?" (recorded 11.11.66) is a breathtaking small-group inside-out jazz session. but what Blue Note record from this period and general category isn't? these sessions are just too much for me sometimes: how is it that every one of these players--here it's Cherry, Pharoah Sanders, Henry Grimes and Ed Blackwell--have such a strong identity and concept, that it's Cherry's session, but everyone contributes such a unique sound. this is living jazz. Grimes gets a lot of solo space and he sounds amazing--really extreme dexterity and outness of concept. my favorite piece i think is "The Thing," which is this awesome bluesy piece--supercatchy, like so many of Cherry's pieces. Pharoah digs into this one so hard. he does a lot of screaming/overblowing, what have you on this disc, but on this one, he just grooves. Ed Blackwell is a true great--his blinding speed and just sense of hurtling along is basically unparalleled. when you wanted the music to just move/cook/etc., you called this guy.

i'm so stuck on this period of music. basically all of my favorite jazz albums date to around this time: all the great Andrew Hill's, the Sam Rivers's, "Out to Lunch," the early Miles quintets, "Interstellar Space." Booker Little's "Out Front" and the Five Spot sessions w/ Dolphy are a few years earlier, but it's really like '59-67 or something. shit was just ridiculous during this time.

*****

hey, a quick thanks to my friend and colleague Steve Smith for linking here from his blog, Night After Night, which is a really cool and diverse resource for opinions on all kinds of music. link is way up there to the right where the links begin ("Steve Smith's blog")-->

kinda nervous to be connected from there b/c that blog and many of the other ones that Steve links to are pretty serious, pro-type endeavours. not really sure what this one is. been very irregular about posting and also, everyone should know that this is really in theory the news page for my band, Stay Fucked [ED: this post was originally on the Stay FKD page, but actually, you're now reading this on the Hank alone blog.] though a lot of the posts end up being about shows i've seen or records i'm listening to. basically it's just about me as someone who makes and listens to music a lot. ok--again, thanks Steve.

strange record to think about: Van Morrison - "Veedon Fleece"

*****

Sunday, October 15, 2006

EVAN PARKER

had the good fortune of seeing Evan Parker play solo saxophone for the second time in my life tonight. this was at the tiny Stone. this was, not surprisingly, completely awesome. some quick thoughts:

a) i think about Parker's sound as consisting of a main sound and a residual sound, the latter coming across to me like sonic exhaust, like it sort of shoots out the back as he's playing the main line.

2) his tenor sound has an amazing bite to it, just very gruff and scratchy. in such a small room as the Stone, it had a huge impact.

d) four pieces were played, plus a tiny encore of "Played Twice" by Monk, which i took as a nod to the recently deceased Steve Lacy, who performed that tune on his 1960 (is that right?) LP, The Straight Horn of Steve Lacy. Lacy obviously being a fellow soprano master--the two played together on that Chirps disc which i honestly haven't heard but need to.

H) Parker showed an awesome sense of pacing. the pieces were long, but they ended when they needed to. an interesting contrast with the Cecil show earlier in the week was that Parker seemed to end pieces in a very deliberate manner, like bringing them down dynamically, whereas Cecil would stop very abruptly. both players give the sense though of dipping into this infinite stream, like it's just a constant flow that you're hearing part of--nothing really begins or ends. both can sound repetitive and constantly fresh at the same time--bringing to mind that idea that i heard quoted once that "Cecil Taylor has been playing the same piece of music since the '70s." it's at once dead on and totally false. Parker's the same way--the music is unmistakable and the basic materials are the same but each piece has it's own logic and the really great ones seem totally unique. for example, one of the tenor pieces tonight had this really key melodic element; Parker jumped between registers and created a nice contrast, something almost hummable. strange b/c i don't think of Parker as being about melodies, but about like liquid pitch changes. the sound is like mercury, constantly burbling or gurgling or flowing in this slippery quicksilver way.

1) listening to the sort of "exhaust" pitches described above is a really cool experience. at times, i detected these very regular rhythms happening "behind" the main note flow, like pulses of 5 or 6 beats. it makes me wonder if there's a limit to how much of each level of sound he can control when doing multiphonics, like if it's the sort of thing where when one layer is shifting, the other must remain constant. sorta like a Heisenberg type of thing.

there is endless mystery in these sounds. time spent communing with Evan Parker is like brain floss, totally bracing and wondrous.

thinking about a lineage about such obsessive musicians, who pursue this one ultraspecific sound--though as stated above, with marvelous microcosmic variation--over an entire career. saw two of these types, Evan and Cecil this week. i believe that Mick Barr of Orthrelm, etc. is this type of player as well. you always know it's him and even though his works are very diverse (especially the Ocrilim record), it's still all pointing toward this basic vibe--laser focus. who else? ... are there artists in other mediums? like Rothko or Mondrian or something? something to think about...

*****

Friday, October 13, 2006

CECIL TAYLOR / XIU XIU

got to see...

Cecil Taylor

last night.

solo.

at Merkin Hall.

i guess you could say this was one of those check-that-off-the-list-of-things-to-do-in-this-lifetime kind of shows. the best thing about it, for me, was the chance just to do my best to home in and listen really really hard to him for over an hour. obviously i have like 100s of hours of his music on CD, but when you're at a concert, that's all you're doing. sounds obvious, but i was thinking about how that's the best thing about live music, not that it's live, but that it gets your undivided attention--insofar as anything ever does. maybe i just have ADD, but it's just special to me to be able to focus so much.

anyway, he played i think four pieces, interrupted by very brief breaks, during which he turned the pages of what i guess was some sort of score resting on the piano, though it could have been poetry. he recited a short poem before playing which was really awesome, one of the more coherent texts i've heard from him. it was printed inside the program notes and contained stuff about "coefficient of viscosity" and "coriolis" and stuff like that. sounds absurd, but it started w/ (get this) the names of five drummers: Chick Webb, Sunny Murray, Andrew Cyrille, Max Roach and Tony Oxley. so to me, the whole poem was about rhythm. really fascinating.

anyway, the music. i'm avoiding trying to describe this b/c it's so hard. ok, Cecil's music is instantly recognizable b/c you have these sort of musings in really short units where the fingers of his right and left hands will mirror each other. those are the connective tissue of his recent solo music. and then there are obviously the percussive parts, where he'll use either the side of his hand, his fists, or his fingers in kind of a rapid-fire downward stabbing motion. and there's also the really dramatic, usually low-end chords that he often slams on in between the aforementioned spasms.

last night was generally in keeping w/ the Cecil solo i know. in the first piece, he seemed to take a bit to build momentum and toggle somewhat predictably between the modes described above. the second piece was fascinating though b/c at one point, he was clearly playing a written figure--he stared at the "sheet music" and repeated this flowery subtle melody three or four times. there were these strange moments throughout the show where he dropped just the slightest hint of a beautiful, consonant melody and then pulled back. at one point, he paused and i actually felt him hesitate: his fingers were shaking above the keys before he plunged back in. also, he was wheezing audibly throughout--a reminder that he is in fact 77 (!!!!) years old.

dammit, i lost my train of thought, but i was going to comment on some interesting features of the fourth piece. i think some similar stuff was going on in terms of these isolated moments of more conventional beauty than i'm used to hearing from him. this is not to say that i'm one of those people who characterizes him as some basher and is surprised to hear something beautiful from him--far from it. but there was some really delicate, quiet playing in this set. during those parts you could really admire how athletic his hands are. he seems to put as much bodily thrust into his quiet attack as to his loud one. the fingers really dance.

this is the way to experience Cecil. just a beautiful thing to be able to witness. can't imagine ever not being completely awed by this man's music.

*****

ran down to the Mercury Lounge to catch Xiu Xiu afterward. this is the band responsible for what is, i think, definitely one of the best albums released in '06, that being The Air Force. the live show was really, really intense, though i'm not sure i prefer it to the records--really it was a totally different thing. on the album, the music envelops Jamie Stewart's voice, but never overwhelms it; the timbre and lyrics are always right up front. live, unless you know how the vocals go already, you might have a hard time making out just what he's up to b/c this was LOUD stuff with the instrumental interplay taking center stage. and awesomely rhythmic i might add. lineup was: Stewart on vocals, percussion, lap steel, etc.; Caralee McElroy on vox, melodica, samples and probably a whole lot of other stuff; and Ches Smith on drums, percussion and vibes. they played over backing tracks, but got into some really heavy syncopations and rhythmic workouts that reminded me (duh!) of Aa a little bit. Ches did a great job of working with the drum machine and playing what sounded like really powerful, fucked up versions of those crazy 32nd-note dance beats you hear in Destiny's Child and shit like that. Stewart is pretty awesome to watch; he's obviously digging pretty deep and he shuts his eyes tight the whole time. a great show, definitely. it's cool that they're sort of interpreting the album rather than reproducing it.

like i was saying, "The Air Force" is definitely something to hear.

*****

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

CANNIBAL CORPSE/JIMMY LYONS/BROTZ and BENNINK/JOHN FEINSTEIN/THE DEPARTED/

CHEER-ACCIDENT/COSMOS

in the All Music Guide's review of the new Cannibal Corpse disc, "Kill," the writer refers to them as a black metal band. ouch.

that album is pretty savage, though it gets totally old after three songs. all the players have gotten a lot better than the last time i really checked them out, which was in like eighth grade, around the time of "The Bleeding" (as you can see, they've really got this album titling thing down to a science). i remember my mom said she would buy me an album if i went on a Sunday school retreat and the one i wanted was fucking Cannibal Corpse. thanks, mom!

also in the middle of this alto thing. been enjoying disc 1 of the Jimmy Lyons box set (thanks Scofield for the burn) immensely. it features this drummer Sydney Smart who may be one of the most cooking freetime pulse players i've ever heard--just complete frenzy, but at a simmering temperature. he sounds like he must have been a pretty crazy dude. or maybe really well-adjusted and he just had this crazy side to him. anyway, where are you Sydney Smart? the first track is a boiled-down burner of ridiculously fast and potent freeness, sort of a la Ornette, but sometimes i like listening to Jimmy even more. Raphe Malik is killing too. Lyons's control is scary, obviously translating those superfast liquidy runs a la Bird to the free thing. but that's really the truth. he is that good. also digging Burnt Offering, recommended to me by my free jazz source Russ Baker. [ed: intended to add that i'm now moving on to "Porto Novo," which pairs one of my other alto heroes, Marion Brown, with Han Bennink, mentioned below.]

who, like me, attended one of the Brotzmann/Bennink sets the other night at Clemente Soto Velez. they really cooked. "track" lengths were a little skimpy, but Bennink's chops made me wanna barf. Brotzmann's tarogato was like an annoying little kid wailing. i love the burr of his tone. made me go back and check out "Reserve," this great FMP disc w/ Barre Phillips and Gunter Sommer. basically i feel that Brotzmann is just a texture--you can turn him on or off and he will go and sound really awesome. not so interactive though. don't know how much that matters when all is said and done. though there are some nice quiet bass clarinet passages on "Reserve" that kind of debunk all that. it's not an absolute thing.

"The Departed" was great. i like Matt Damon's Boston accent and boyish macho thing so much. look out for the scene where he picks up the lady shrink in the elevator. he says something like he'd get stabbed in the heart with an icepick if he could go out w/ her. and then the actual date scene is amazing, with both him and her commenting on this weird architectural dessert. most will comment on Nicholson, but it's the painful scenes between Damon and the girl that got me. plot is SO confusing, like "Miller's Crossing" but worse. very brash and audacious, if at times predictably so. whatever, you'll love it.

reading John Feinstein. i love his books about sports. i could give a shit about the Baltimore Ravens, but he writes characters so goddamn well. i love the narratives. proves my point about nonfiction: any documentary work is interesting if it's well told. the subject is totally irrelevant.

Cheer-Accident is coming to town. hail this band. listen to "Learning How to Fly" from "The Why Album" or "Find" or "Smile" from "Introducing Lemon." their drummer/pianist/vocalist/trumpeter Thymme Jones is an utter progpop genius. he plays these sick funky oddtime beats and sings in this beautiful sort of neutered whine. that's not a good description. it's just a pretty high croon sans drama. melodies are something like Beatles meets Yes. hail hail hail this fucking band.

enjoyed Cosmos at ErstQuake. tiny sounds. people laughed at me when i described it. Ami Yoshida is a poet of the throat and a very sad performer to watch--sad as in full of pathos. amazingly austere yet fragile. don't wanna get into stupid cliches re: her gender and ethnicity. listen to Cosmos.

looking forward to: Peter Luger, Cecil Taylor, Xiu Xiu (AMAZING new album), playing the new Stay Fucked song live--it's called "Naked from the Waist Up" and we've had some of the riffs kicking around for several years.

other things of note:

Ocrilim - Anoint

Point Break on DVD - Ultimate Adrenaline Edition

Steely Dan - Making of Aja DVD

The Band - Making of "The Band" DVD

some people that i have encountered recently, both for good and for bad...

MELVINS/BLUE NOTES

the new lineup of the Melvins proved itself a smashing success w/ the recently dropped "(A) Senile Animal," but they sealed the deal big time at Warsaw tonight. the show simply kicked total ass.

openers were weak to piss poor. i'm a huge fan of Joe Lally's bass playing in Fugazi, but his solo stuff doesn't do much for me--basically very chill songs built around bass vamps and Lally's speak-singing. the songs he sang on the last three Fugazi records were awesome, but these just feel half-baked. it was interesting to hear him backed by Dale Crover and Coady Willis of the 'Vins and (of all folks) Melvin Gibbs on "lead" bass, but the set was pretty much a snooze.

Ghostigital (i think one of the dudes from the Sugarcubes) just totally blew. boring arty dance music w/ rambling poetry over top.

then was Big Business who played a really solid set of mostly new stuff. this was the first time i heard them live where the mix was just right. their music is straightforward and relentless and, it must be said, very Melvins-like, but they've got a really strong identity, owing to what awesome players Jared and Coady both are. the notsosecret weapon is Jared's voice, a hugely powerful and melodic instrument. Dale joined in on guitar on a few tracks including "Easter Romantic" from "Head for the Shallow" ("White Pizzazz" was also played, after Dale exited), which i thought was probably the best heavy record of '05.