Friday, March 26, 2010

Six songs

Offered without comment. Just really been wanting to share these recent obsessions. Wish I had web storage space, but for the moment, I don't, so video embeds will have to do. The artists are, respectively, Chatmonchy, Death (Detroit, not Florida), Xiu Xiu, Cynic, the Outfield and Looker.

Friday, March 12, 2010

Maynard James Keenan's Puscifer at the Grand Ballroom: The curveball that could

Photo: Isaac Brekken

I've been a fan of Tool for a really long time. Like most, I came on board in '93, when "Sober" hit Headbanger's Ball. I lost track of the band for a while during college, but when I checked back in with them in the early aughts, I was pretty blown away by what had emerged in the interim, specifically Lateralus, an absolute classic of the dark-and-epic-rock mode. I grappled with 10,000 Days when it first came out, but I've since come to accept it as mostly awesome, and I can't wait till the band reactivates.

It almost goes without saying that Maynard James Keenan's voice is one of Tool's key features for me. I'm sure this is true for the great majority of fans. There's just something alchemical in the way his sinuous chant mingles with the band's crisp roboprog riffs.

Even so, I cannot say I had terribly high hopes for last night's Grand Ballroom show by Keenan's latest side project, Puscifer. (Check out my friend and colleague David Fear's excellent Q&A with Keenan to get up to speed, and note also that Puscifer performs again on Saturday at the Apollo.) Prior to the gig, my exposure to Puscifer was minimal, just a few press releases over the past few years and some promo CDs that I'd never brought myself to engage with. Why? Simply, it was the humor that did it. As any music fan knows, humor can be the ultimate moodkiller. It's not that humor doesn't belong in music; it's that when humor exists as part of whatever artist's palette, it too often overwhelms any other element that might be present. It's alienating, mainly because if you don't happen to find a particular artist's brand of humor funny, you're likely to be turned off the entire endeavor. Everyone has an example of this. For me it's Zappa. I know there's some substance there, but I find his pervasive comedic element completely insufferable: smug and cheesy and dated and just the ultimate turn-off. Maybe one day I'll go there, but so far, the funny-stuff armor has kept me far away. (It goes both ways, of course: Such accusations could certainly be leveled at two of my favorite bands, Ween and Cheer-Accident, but the difference for me in both cases is the almost sadistic mingling of light and dark.)

Anyway, so in sum, I heard some years back that Keenan had a side project called Puscifer; I learned that the band's debut album was entitled "V" Is for Vagina; and I checked out the asinine cartoon cover art. In short, I snap-judged the hell out of the thing, deciding that this sort of goofing off was just not what I wanted from Keenan. After all, don't we, as fans, have the right to decide what to consume and what to pass on? Sure, perhaps I had typecast Keenan, deciding that I'd turn to him for dark and sumptuous, not silly and irreverent, but this is not an uncommon move. We all do the same thing: We want X mood or vibe from X artist and we don't want curveballs, even if said artist is "challenging" or whatever. I believe I'd be just as initially dismissive of the idea of a comedic project from, say, Cecil Taylor. (Or, for that matter, a dramatic project from, say, Aziz Ansari.)

As for last night's show, let me say two things definitively.

One: The humor aspect was indeed pervasive and often unfunny. The entire performance, a sort of multimedia revue complete with costumes, video interludes and dramatic "business," was structured around a fictional airline called Vagina Air, a conceit that provided a platform for all sorts of stale jokes about post-9/11 air-travel paranoia and the like.

Two: The music was so fantastically cool that it was nearly impossible to care. In other words, I really underestimated Keenan. Amid all the silliness, there were these incredible songs: jauntier, groovier, hammier, simpler and in many ways catchier than Tool--I'd describe it industrial-, cabaret- and metal-tinged art pop--but still very driving and still perfect vehicles for Keenan's voice. And oh, that voice... Like the rest of the cast (there were seven or so people onstage), Keenan spent the entire show in a pilot's outfit, complete with shades. He sang mostly from behind a video screen--see above--which projected his face as a sort of fish-eye caricature. But none of this detracted from his performance. I'm not kidding: He sounded absolutely stunning, yielding perhaps the most just-like-the-record live vocal sound I've ever heard in my life. I'd seen Tool a few years back but the mix was terrible and Keenan was largely inaudible. At this Puscifer show, the sound was PERFECT and you could hear every contour, every warble, that haunting sing-song you'd heard so many times on albums. Laal (also a huge Tool fan) and I kept turning to each other with mouths agape, one or the other of us exclaiming, "I seriously cannot believe how good he sounds."

And the material, though unfamiliar, was an excellent vehicle for Keenan's gifts. Most of it was swaggery and driving, pitched right between the sinister and the playful. But some of it was downright balladic, with a distinctly loungey feel, with Keenan coming off like a histrionic though entirely sincere Vegas crooner. The music and the presentation had a gimmicky element, but crucially, Keenan played it straight and sang his ass off. (To be fair, the band ruled, especially the really solid, crushing drummer and an excellent female vocalist--Carina Round--who served as an excellent foil for Maynard.)

The stunning quality of his performance had the really remarkable effect of legitimizing everything around it. Gradually, all the cheesy video interludes came to seem delightful; the theatrical hubbub going on simultaneous to the music began to come off like a charming complement to the already vaguely Broadway-ish material. (Former Primus drummer Tim Alexander played the role of a flight attendant, while opening acts Neil Hamburger (!) and Uncle Scratch's Gospel Revival sat in faux airplane seats at center stage, chatting, drinking and reading the paper during the majority of the performance.) Overall it was like watching a performer jump the shark, but doing so in such a professional and expertly choreographed fashion that the joke was on you for trying to put them in an aesthetic box in the first place. You actually felt like you were being forced to accept an aspect of Maynard James Keenan that you weren't ready for and you couldn't help but be won over.

Think about this for a second: When was the last time an artist actually won you over with a complete curveball? That's a mixed metaphor, but you know what I'm saying: It's a pretty profound thing when you see something so cool that you lay down your bias then and there, conceding, "You know what, you're right. This is in fact awesome." Again, as I said above, an unfunny attempt at humor may be the most profound turn-off in art, but I left this show completely convinced that Puscifer is every bit as legitimate an outlet for Keenan's singular gifts as Tool. Strong words, but I'm serious.

It seems like such a simple concept, this notion of being challenged, but I really don't think it is. Even with dark or abrasive art, we usually want a certain thing and we get that certain thing and we're happy. We say we want a challenge, but we want it on our terms, deciding when we want it and from whom. Whatever your feelings on Puscifer, the project poses an aesthetic challenge to Keenan die-hards (and there are many far more rabid than myself), and moreover, it actually rewards the effort. It's not a curveball for curveball's sake--it's a very fruitful outlet for a guy who just happens to display really schizophrenic artistic tendencies.

Now I'm going to have to dive into Keenan's other other band, A Perfect Circle, which I've barely heard. I can only hope I'm initially completely repelled by what I discover.

Labels:

A Perfect Circle,

Carina Round,

Grand Ballroom,

Maynard James Keenan,

Puscifer,

review,

Tool

Sunday, February 28, 2010

The point

A phenomenon I treasure, experienced twice this weekend: when a piece of writing about music sends me scurrying, more or less frantically, to listen. It's like a command. Two CDs I'd had for ages, lying amid the innumerable stacks in my room, and to which I'd never paid ample attention. Two writers, persuading and prepping me. Thanks to Alex Ross, I dug into the stark but inviting Xenakis Percussion Works, and thanks to Howard Mandel, I spun Ornette's fantastically exuberant Friends and Neighbors. Reminders that, yes, there is a point to this endeavor, and the point is to point, to make a case for why, even in the midst of info overload, you should really take a minute to check this here thing out. Ross puts it as succinctly as it could be put when he titles his forthcoming book Listen to This.

Thursday, February 18, 2010

Sunny Murray's time now (and then)

Where are they now, the still-living architects of free jazz? For one, they're in Sunny's time now [sic], a 2008 documentary about Sunny Murray that has just reached me on DVD. The descriptor "sprawling" was invented for films like this: It's all over the place. Sometimes rambling, sometimes pointed, but for anyone who's into this stuff, it's riveting, mainly because of the cast.

Everyone is here. It's like a family reunion. Sonny Simmons, Grachan Moncur III, Henry Grimes, William Parker, Bobby Few, Cecil Taylor, Tony Oxley, Robert Wyatt (?!) and tons of others whom I was either unfamiliar with or knew only marginally: François Tusques, Tony Bevan, Fritz Novotny and more. And then the scholars and scribes: Val Wilmer (hail), Ekkehard Jost, Tony Herrington, etc.

All assembled to illuminate a difficult personality. I adored Sunny Murray, and then I caught him live at Tonic in October of '04 with Sabir Mateen and Dave Burrell, a gig documented by Eremite but which I could barely stand to relive. Without going into detail, Murray appeared in a visibly altered state and after Burrell took it upon himself to bring some much-needed focus to a wholly disjointed and directionless performance, the drummer stood up, tapped the pianist on the shoulder and stopped him cold. Cecil Taylor recounts the incident in Sunny's time now and seems to have found it amusing. To me, it was a travesty: Burrell chose to take the gig seriously and Murray didn't, and that was that. (I hate to slander anyone, but sometimes the facts are the facts, as this review of a Murray performance from last June attests: "...Sunny Murray spent most of the performance stumbling off his drum stool, lurching through the crowd and talking loudly while [Odean] Pope gamely tried to keep some semblance of a concert together. Left to himself for most of the gig, Pope padded time with a lecture and demonstration on Clifford Brown. Just as he was wrapping it up, Murray staggered back to the stage and grabbed the mic. “I just want you to know, I’m not drunk,” he asserted in a slur....")

So I've had some mixed feelings re: Murray over the years, and for a while I couldn't even listen to him. But who could stay mad at The Copenhagen Tapes or Nefertiti, the Beautiful One Has Come? And then I started to warm up to the relaxed splendor of the later work, especially the amazing Dawn of a New Vibration, a 2000 duo session with Arthur Doyle on Fractal. (A contemporaneous example of that badass partnership is here.) There just wasn't much point in staying mad at Sunny Murray.

The film doesn't shy away from Murray's foibles. Murray's son, who shows up in a few brief interview clips, expresses a bit of pride at his father's renown but even more vexation re: Dad's uneven temperament. Cecil Taylor, in his inimitably catty way, provides more evidence of same. And rehearsal footage of an insanely star-studded large-ensemble gig in Luxembourg depicts Murray as impish and distracted.

But there's so much to love and to marvel at here. Try a duo concert with Bobby Few, like the entire film, beautifully shot and recorded. Try the aforementioned Luxembourg gig. We only get a few segments, but dear God, the lineup: Murray, Grimes, Moncur, Few, Simmons, Pope, Rasul Siddick, Tony Bevan and more. And--so poetic and humble and real, I can't even begin to express--a small-group version of "Round Midnight" from a Paris club gig with Simmons, Few and some others. Tons of jazz musicians come full circle, moving through free jazz and back into standards, but rarely do they re-address the tradition with such grace as these expatriate free-jazz types. Simmons and Few, I already knew about, but Murray is such a good match for them. His restraint (perfectly content to wisp about with brushes) will astound you. Some very intrepid and enterprising producer needs to get these three together for a trio session pronto.

There's also so much here that has nothing to do with Murray. Little scraps re: the European and British perceptions of American free jazz. François Tusques praising Archie Shepp for his political awareness and mocking Frank Wright for his political ignorance. Val Wilmer going through old Murray photos she took, admiring how they capture his intense (and, she asserts, unusual for the idiom) love for his family.

Again, a mixed bag, but an essential one. The performance footage is golden. Loved seeing/hearing Murray in duet with Novotny, a soprano sax player with whom I was totally unfamiliar. And the concluding presentation of the Murray, Bevan and John Edwards trio is a mindfuck, full of brawn and sweat, but also grace. Didn't care for Spring Heel Jack contributions or another gig featuring unfortunate electric bass, but it all just hangs out there and becomes part of the film's weird patchwork quality. Maybe it's because Murray himself isn't directly interviewed (he is on the bonus disc, though), but everything here feels like a tangent. Fortunately many of these tangents also register as revelations.

But as I (tried to) indicate above, what will stick with you are the personalities of these still feisty old men, the immense variance. Simmons's absurdly charming rakishness, Few's heart-melting sweetness, Moncur's mercurial oddness, Taylor's relentless superciliousness. What an unbelievably diverse bunch of men, these first-wavers. This film's greatest triumph is to place all these artists in the NOW. We know them from records, and we often fetishize their discographies over their physical presences. (As the Murray gig I described above indicates, sometimes the artists have given us good reason to do so.) But they still have a lot to tell us.

Sunny's time now, yes. But it's also the time of all the others who lit the fire in the '60s and kept raging, albeit in a sublimated way. Think of Bill Dixon, whom I just listened to today in a fantastic trio with two young improv masters. Think of the aforementioned Dave Burrell, whose recent records are some of his very best.

In Murray's case, it's somewhere in between. For sheer ecstatic insanity, you're not going to beat his early work. But when he manages to keep his composure these days (the Bevan/Edwards band seems like a particular good focusing agent for him), he's really got something going, a droopy dance, the pinnacle of unhurriedness, following buzzy, uneven snare rolls with clumsy yet thunderous thwacks on bass drum and crash. And (as you can hear in the "Round Midnight" I mentioned above) a tremendous respect for song form, for contour, and (again, when he's behaving) for his fellow players. In the majority of the live footage in this film, he is, in fact, behaving, and accompanying in a remarkably sympathetic fashion. So if nothing else, the film helped me to further forgive Murray for the disastrous 2004 gig I'd caught. We may only get sporadic brilliance from Murray these days--a statement that applies to several of the aforementioned early-free-jazz survivors--but the good stuff is worth the required patience.

Anyone else have any similar stories of resentment and/or redemption re: first-wave free-jazzers, i.e., seen players of this style, caliber and age turn in either notably subpar or phenomenal gigs? I feel like this unpredictability is something every free-jazz fan has dealt with at one time or another.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Canceled? Check

Bummed, bummed, bummed. Steeve Hurdle—see previous post—has canceled his Stone appearances for tonight and tomorrow. That makes two for two, re: 2010 shows I was looking forward to like Christmas morning (Hanukkah night, technically), and which I previewed in TONY, only to have them called off. Lest I curse another gig, I do hereby (mock-)promise not to go out of my way to prepublicize the next NYC show I'm dying to see. In the meantime, ALL and Steeve Hurdle, please reschedule soon!

Sunday, February 07, 2010

O Canada

Not unusually, I have Canadian music on the brain. Thinking about the marvelous spectrum. This evening I reveled in "Last of the Blacksmiths" and "Sleeping," and read up on the upcoming Rush documentary (codirected Sam Dunn, the man responsible for the oustandingly diverse Metal: A Headbanger's Journey). Topped it all off by indulging my current obsession with the joint work of Luc Lemay and Steeve Hurdle, the latter of whom is (I seriously can't wait) headed NYC-ward in a week's time. Feel it:

Labels:

Canada,

Luc Lemay,

Richard Manuel,

Rush,

Sam Dunn,

Steeve Hurdle,

The Band

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Masterful class: Fly at Manhattan School of Music

[Image above: Ed Ruscha]

"This is kind of a personal question, but does music ever scare you?" A Manhattan School of Music student posed this unconventional inquiry on Monday toward the end of an afternoon master class with Fly. The musicians seemed slightly caught off guard, but they dove in. Drummer Jeff Ballard recalled being severely freaked out by what he referred to as the "bestial" energy of a recent Sam Rivers recording. Saxist Mark Turner, whose calm, cryptic responses throughout the afternoon had a strong Zen aura, grinned faintly and answered, "Yeah, it does--and I kind of like it."

I stumbled into the event pretty much by accident. As previously reported, I had been meaning to catch Fly this past weekend at Jazz Standard, but it didn't work out. I wrote the group's publicist Monday morning to ask if they had any more gigs coming up and she mentioned that I was welcome at the MSM session that very day. I had to scramble a little to make it uptown, but I'm very glad I did.

Prior to this, I wasn't sure I even understood what went on at a master class. What transpired wasn't terribly different from what I'd expected: The band simply alternated between performing a tune and pausing for discussion and Q&A, a process that repeated for 90 minutes. To some the lengthy spoken interludes might have distracted from the music. I found them enthralling. Often when audience discussions go down at concerts out in the real world (i.e., outside of academia), you get a lot of audience members trying to impress one another with their supposedly sophisticated or insider inquiries. I picked up none of that from the MSM students. They seemed genuinely fascinated by Fly--their motivation was to learn, not to show off.

The talk got technical at times, but mostly it was philosophical. The band members' mini treatises on improvisational problem solving seemed only incidentally music-related. When one student asked about the players' conception of the beat, Ballard and bassist Larry Grenadier each dove deep into metaphor, with the former likening time to a curtain ("The time is draping") and the latter comparing it to a circle with the strict metronomic pulse in the center and all sorts of fruitful approximations surrounding it. The musicians returned often to the idea of tension and release, specifically the notion that supposed musical freedom means little unless it's juxtaposed with structure. Without some kind of framework to serve as contrast, Turner ventured, "The obscurity is no longer obscure." Ballard put it another way: Of musical freedom, he joked, "It's not free--it costs a lot.

Also, fascinating insights into process, preference, personality. "How did you find your sound?" Ballard struggled with his words and then simply began striking different parts of his kit--a tap near the edge of the untightened snare, a thwack to the metal rim of the tom--by way of demonstrating that he simply focused on the timbres and textures he enjoyed most. When someone asked about listening preferences, Ballard and Grenadier chided Turner for his love of Depeche Mode and Echo and the Bunnymen. ("It's true," Turner professed.) Later the notion of musical personality or "concept" came up again and things once again turned reflective. Turner, a former visual artist (anyone know what particular medium he worked in?), discussed how that pursuit had come much easier to him than music and how a part of him wished he'd stuck with it. As for the notion of a concept, he was typically reticent: "I don't think I have a concept yet."

You'd never hear this sort of stuff in a jazz club, and that's probably appropriate: A lot of patrons wouldn't be interested in a hour of analytical discussion mixed in with their music. On the other hand, though, I think a lot of fans of jazz--or any other style of music, for that matter--would like to see this kind of performer/audience interplay go down outside of academia. I'm sure there are series around NYC that approximate this dynamic, but I know there's room for the model to expand further. Personally, I find it fascinating to witness musicians both practicing *and* preaching.

And speaking of practicing, the music Fly played on Monday was glorious--filled with brain-teasing restraint and forms that initially sounded conventional but later revealed mystifying idiosyncrasies. Re: this lopsided account, I don't mean to short-shrift what was played; I just wanted to point out that the talking seriously enhanced my enjoyment of the music. If it turns out that Fly-caliber jazz artists give master classes regularly at MSM, I might have to start paying tuition.

Friday, January 22, 2010

Feeling Fly

If you stripped the term "smooth jazz" of every single negative connotation, and then sought out the epitome of what those words actually mean, you might find yourself obsessing over Fly, as I currently am. If I'd have spent due time with this trio's 2009 release, Sky and Country, it probably would've placed a lot higher on my year-end jazz list. The album has mystified me over the past days: so wispy that it recedes into the background with even a moment's lapse of attention, but so sturdy and engaging if you can manage to focus.

Saxophonist Mark Turner's sublimated heat and drummer Jeff Ballard's exceedingly delicate yet hard-driving momentum. Bassist Larry Grenadier ruminating or holding it down. Compositions with thorough, convincing architecture. A lot of variety from piece to piece: backbeat, post–second-great-Miles-quintet freebop, hushed prayers, even a crazy drum 'n' bass styled thing. (All rendered on Sky and Country with inimitable ECM classiness: perfectly elegant.) It almost goes without saying, but this is a working band (and one that bills no player's name out front, which I love). This weekend they'll be working at Jazz Standard. Jim Macnie has some brief words of praise and a great video. David Adler wrote a nice profile for TONY last year. [After writing this, I discovered some strong recent live recordings on the Fly MySpace.]

/////

Also: Tonight, Hexa and The Octagon share a bill at Bruar Falls. Both bands feature good friends of mine and musical collaborators past and present. I'm biased but both also create outstanding modern guitar-pop music. The Octagon has a great new record out on Serious Business--you should definitely pick it up.

Also: Jean-Ralphio. I cannot stop watching this.

Also: Neglected to mention here that Roaratorio has an awesome new limited-edition Joe McPhee LP out with liner notes by me, sourced from this blog post. (The gig you hear on the record is the very same one I wrote about.)

Friday, January 15, 2010

Lately

Anyone got any solid suggestions re: where to donate for Haiti relief? What a terrible thing this is.

/////

Two exceedingly less important items of business:

*My review of last night's Julian Casablancas show at Terminal 5, with pics by Laal. A solid show, one that did justice to Phrazes for the Young, which I love (especially "11th Dimension," "Left & Right in the Dark" and "River of Brakelights"). Apparently, Julian is a big Alicia Keys fan.

*My brief commentary on last weekend's smashingly successful Winter Jazzfest. Top discovery of the night: J.D. Allen's ultra-sick trio. I know I'm the last one on the Allen bandwagon; glad to find that the fuss was justified.

Friday, January 08, 2010

Jack DeJohnette at Birdland, etc.

It's the first week of the new year, and it's a busy one, musicwise and otherwise. Coming off a solidly lengthy "winter break"--it felt a little like college again--filled with good people (for one: a dear old comrade, now living overseas, payed a visit with his girlfriend) and a healthy amount of doing-nothing time.

The coming weekend was supposed to be all about ALL. Sadly, the shows--which I had previewed in this week's TONY--have been cancelled, a fact I find mildly devastating. I really hope that whatever's ailing one of the greatest drummers alive abates soon. Fortunately the Winter Jazzfest lineup looks stellar.

/////

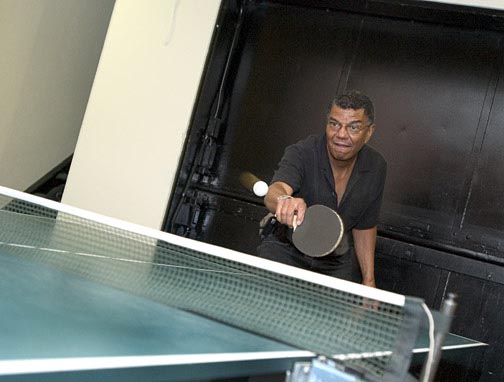

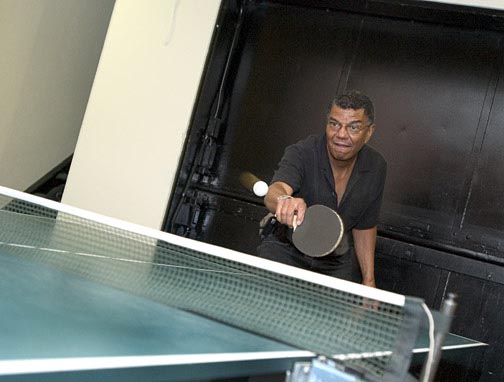

[Jack DeJohnette pic: courtesy Celebrities Playing Table Tennis (!)]

Re: Jazzfest, I warmed up with Jack DeJohnette & Co. at Birdland last night. (Thanks to Steve for the multiple Twitter tips [e.g.] on this gig--I didn't even realize it was going down.) A great set, and I encourage you to head down tonight or tomorrow, even if it means missing a bit of WJF. I'd never caught DeJohnette live before, and that was a major draw, but I think what really enticed me was the backing band: Rudresh Mahanthappa on sax, David Fiuczynski on guitar (double-necked!), George Colligan on keys (w/ some serious MIDI vibes, simulating harpsichord, harmonium, organ, etc.) and Jerome Harris on acoustic bass guitar. I wasn't disappointed.

During the first few minutes of the opening tune, "One for Eric"--a classic that debuted on the fantastic Special Edition album in 1979--I was struck by how turbulent the improvising was. Whenever I'm hearing challenging or abstract jazz in a club like Birdland, I can't help but feel for those tourist-types who may have wandered in unawares in search of smooth dinner music. I'll just say I was glad I wasn't dining last night. DeJohnette really smacks the drums, and on "One for Eric" he laid down a rocky, free-time landscape once the solos got going. (He saved the incredibly supple and intricate low-volume swing for the bass solo.)

But the cool thing about DeJohnette as a bandleader and composer is that he makes that kind of wildness feel accessible and fun. The set closer, "Ahmad the Terrible," with its knotty melody and carnival-esque acceleration, registered more like off-the-wall party music than anything foreboding. And even during the prickly unaccompanied Mahanthappa solo--surely the out-est moment of the evening--that preceded the tune, DeJohnette flashed a few grins at Harris, which took a little of the edge off.

The drummer really knows how to construct a set. Last night, in addition to the bookend classics mentioned above, we got "Music We Are," a killer ballad with DeJohnette rocking the melodica in fine, yearning style--weirdly, his sound on the instrument reminds me of the beautiful synth-harmonica theme that accompanies the underwater level on the classic Super Nintendo game Donkey Kong Country--and some chaotic rubato poetry, "Dearly Beloved"-style, from the ensemble. Then, "Spanish Seven," a fast Latin-y romp in said time signature that built into a nasty sort of fusion, part electric-Miles funk and part jaunty klezmer. (I remember Colligan riding the groove with unhinged glee.) And "Ahmad" concluded with an odd Indian-music breakdown, with Colligan providing faux-harmonium and Harris on otherworldly vocals, a little like the higher pitched Tuvan stuff demonstrated here.

So it was all pretty out there but also down to earth. Challenging, but without any stone-faced self-importance. Flashy and occasionally even a bit gimmicky in its eclecticism, but not watered down. You left feeling like you'd been in good, honest hands. And somewhat unexpectedly, with less recollection of the individual players than of the band as a single organism. Wouldn't wanna deny props to Mahanthappa's solos (nimble and peppery, with a lot of sublimated freakiness) or Fiuczynski's (effortlessly classy on the fretted guitar neck, sproingy and slightly alien-sounding on the fretless one), but DeJohnette's concept(s) prevailed, and it was one all the sidemen got behind wholeheartedly. I don't know DeJohnette's full discography well enough to tell you how unprecedented this group's sound is within his catalog--in a Voice blurb, Jim Macnie alludes to a 1989 album called Audio-Visualscapes that I haven't heard--but I really think someone should record this band.

The coming weekend was supposed to be all about ALL. Sadly, the shows--which I had previewed in this week's TONY--have been cancelled, a fact I find mildly devastating. I really hope that whatever's ailing one of the greatest drummers alive abates soon. Fortunately the Winter Jazzfest lineup looks stellar.

/////

[Jack DeJohnette pic: courtesy Celebrities Playing Table Tennis (!)]

Re: Jazzfest, I warmed up with Jack DeJohnette & Co. at Birdland last night. (Thanks to Steve for the multiple Twitter tips [e.g.] on this gig--I didn't even realize it was going down.) A great set, and I encourage you to head down tonight or tomorrow, even if it means missing a bit of WJF. I'd never caught DeJohnette live before, and that was a major draw, but I think what really enticed me was the backing band: Rudresh Mahanthappa on sax, David Fiuczynski on guitar (double-necked!), George Colligan on keys (w/ some serious MIDI vibes, simulating harpsichord, harmonium, organ, etc.) and Jerome Harris on acoustic bass guitar. I wasn't disappointed.

During the first few minutes of the opening tune, "One for Eric"--a classic that debuted on the fantastic Special Edition album in 1979--I was struck by how turbulent the improvising was. Whenever I'm hearing challenging or abstract jazz in a club like Birdland, I can't help but feel for those tourist-types who may have wandered in unawares in search of smooth dinner music. I'll just say I was glad I wasn't dining last night. DeJohnette really smacks the drums, and on "One for Eric" he laid down a rocky, free-time landscape once the solos got going. (He saved the incredibly supple and intricate low-volume swing for the bass solo.)

But the cool thing about DeJohnette as a bandleader and composer is that he makes that kind of wildness feel accessible and fun. The set closer, "Ahmad the Terrible," with its knotty melody and carnival-esque acceleration, registered more like off-the-wall party music than anything foreboding. And even during the prickly unaccompanied Mahanthappa solo--surely the out-est moment of the evening--that preceded the tune, DeJohnette flashed a few grins at Harris, which took a little of the edge off.

The drummer really knows how to construct a set. Last night, in addition to the bookend classics mentioned above, we got "Music We Are," a killer ballad with DeJohnette rocking the melodica in fine, yearning style--weirdly, his sound on the instrument reminds me of the beautiful synth-harmonica theme that accompanies the underwater level on the classic Super Nintendo game Donkey Kong Country--and some chaotic rubato poetry, "Dearly Beloved"-style, from the ensemble. Then, "Spanish Seven," a fast Latin-y romp in said time signature that built into a nasty sort of fusion, part electric-Miles funk and part jaunty klezmer. (I remember Colligan riding the groove with unhinged glee.) And "Ahmad" concluded with an odd Indian-music breakdown, with Colligan providing faux-harmonium and Harris on otherworldly vocals, a little like the higher pitched Tuvan stuff demonstrated here.

So it was all pretty out there but also down to earth. Challenging, but without any stone-faced self-importance. Flashy and occasionally even a bit gimmicky in its eclecticism, but not watered down. You left feeling like you'd been in good, honest hands. And somewhat unexpectedly, with less recollection of the individual players than of the band as a single organism. Wouldn't wanna deny props to Mahanthappa's solos (nimble and peppery, with a lot of sublimated freakiness) or Fiuczynski's (effortlessly classy on the fretted guitar neck, sproingy and slightly alien-sounding on the fretless one), but DeJohnette's concept(s) prevailed, and it was one all the sidemen got behind wholeheartedly. I don't know DeJohnette's full discography well enough to tell you how unprecedented this group's sound is within his catalog--in a Voice blurb, Jim Macnie alludes to a 1989 album called Audio-Visualscapes that I haven't heard--but I really think someone should record this band.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)