Sunday, January 03, 2016

Heavy Metal Be-Bop lives

Tonight, after an inexcusably long delay, I posted the 12th installment of my jazz/metal interview series, Heavy Metal Be-Bop: a conversation with master guitarists and longtime collaborators John Dieterich and Ed Rodriguez. You might know these two from Deerhoof, but that's just the tip of the iceberg.

Enjoy, and Happy New Year!

Friday, February 28, 2014

DFSBP archives: Whit Dickey

During my interview with Andrew Hock, we talked quite a bit about the guitarist Joe Morris. I hadn't spun a Morris record in a while, so I pulled out a few old favorites in the days that followed, and this listening excursion led me to the latest in a neverending series of drumcentric soundchasing jags—this one focused on Whit Dickey, a frequent Morris collaborator for two-plus decades.

I've always felt that Dickey was a seriously underrated artist, even among free-jazz heads. I first heard him right as I began to explore the downtown NYC scene in the early aughts. I have a distinct memory of seeing him play at the Mercury Lounge, of all places, as part of an improv round robin organized by the Vision Festival crew. I think it was at that show that I approached him to see if he'd be interested in appearing on air with me, for an episode of WKCR's Musician's Show. (DFSBP readers might recall the Grachan Moncur III interview, another installment of the same program.) You can stream—via the blue Streampad bar at the bottom of the page—or download that three-hour program below, split into four segments:

Whit Dickey - WKCR Musician's Show - 5/2/01, pt. 1

Whit Dickey - WKCR Musician's Show - 5/2/01, pt. 2

Whit Dickey - WKCR Musician's Show - 5/2/01, pt. 3

Whit Dickey - WKCR Musician's Show - 5/2/01, pt. 4

I was, and still am, a huge fan of Transonic, Dickey's 1998 debut as a leader—a trio date with saxist Rob Brown and bassist Chris Lightcap. I reviewed it for AllMusic.com way back when. I know I wouldn't frame my impression now the way I did then—"One does not normally look to a drummer-led jazz session for innovative compositions…" (groan)—but I'm still struck by what a strong concept Dickey puts forth on this record. It's not just his writing, which is punchy, concise and memorable; it's the way he drives a band with palpable yet slippery force. Much like the great Sunny Murray, whom Dickey really sounds very little like, his playing acts as a sort of vortex, drawing the music toward it, sometimes very subtly. I feel the same sort of confidence, the same entrancement when I listen to both players, the sense that they're helping to lend a sort of elemental weight to whatever setting they appear in, without having to assert themselves in bombastic ways. This kind of sorcery, or cultivation-of-vibe, if you will—heard in everyone from Motian to Oxley to Graves—is my number-one aesthetic priority when it comes to improv-driven percussion, and Whit Dickey's playing oozes that quality. In the WKCR interview, Dickey talks quite a bit about environmental vibration, and how he seeks to translate what he hears around him into his playing; that might sound like mumbo-jumbo, but if you listen to enough of his work, you'll understand exactly what he means. (On the other hand, he also discusses his studies at New England Conservatory, so there's more than intuition at work in what he does.)

I actually know what are probably the best-known Dickey records—his collaborations with David S. Ware—the least well. I reserve a special place in my jazz pantheon for his leader dates: Transonic; its follow-ups, Big Top and Life Cycle (credited to the Nommonsemble); the extraordinary and hard-to-find Prophet Moon (by Trio Ahxoloxha, i.e., Dickey/Brown/Morris, the same trio heard on the earlier Youniverse); the more recent Coalescence (with Brown, Morris [on bass here] and the late Roy Campbell Jr.) and Emergence (with Daniel Carter and Eri Yamamoto); and, a record I've just discovered, Understory, a super-earthy/emotive 2013 collaboration with Sabir Mateen and Michael Bisio under the Blood Trio moniker. (I haven't yet spent good time with the handful of recent Ivo Perelman records on the Leo label that feature Dickey, but those are definitely on my list.) These albums could all be considered part of the free-jazz continuum, stretching from the ’60s ESP cats up through the ’90s Aum Fidelity / Vision Festival cohort and beyond, but thanks in large part to Dickey's presence, they embody a special kind of sonic poetry. He's among a select group of improvisers whose affiliation with a given session makes the record in question an instant must-hear for me.

The Aum Fidelity website identifies Dickey as a "somewhat mysterious figure." As you'll hear, he was perfectly friendly and forthcoming in the interview setting, but I understand what that description was getting at. Dickey's never been much for self-promotion; to this day, he doesn't have a real Web presence, and I always seem to hear about his releases and gigs after they occur. (It's worth noting too that there don't seem to be any other interviews with him online.) It's been a good while since I've seen him live—I caught a great show by Matthew Shipp's trio, which includes Dickey and Bisio, at the Stone probably four or five years back—and I hope to remedy that soon. In the meantime, there's a substantial body of recorded work to savor. You'll hear a nice sampling from both Transonic and Big Top in the WKCR program—as well as Dickey-curated selections from his favorite drummers, including Steve McCall, Freddie Waits and Milford Graves. To complement that, here's a good chunk of Whit Dickey on Spotify:

Monday, December 02, 2013

Chico Hamilton, 2006

In 2006, I spent an afternoon at Chico Hamilton's apartment, interviewing him for Time Out New York. I was underprepared; he was ailing and rightfully impatient. The conversation limped along until I mentioned, in quick succession, that I was 1) from Kansas City and 2) a drummer. The Q&A is no longer on the TONY site, but after I heard about his passing, I dug it out of the archives and transcribed it.

I still don't know Hamilton's music as well as I'd like to. I do love what I've heard of the early quintet material, and about a year ago, I caught a few pieces off Man from Two Worlds (a ’63 Impulse set with Charles Lloyd and Gábor Szabó) on WKCR and sat spellbound. The only time I saw Hamilton live was at the 2011 Winter Jazzfest; here's my mini review:

"I'm happy to be here.... At my age, I'm happy to be anywhere," joked 89-year-old drummer Chico Hamilton from the stage, before offering a textbook demonstration of how swinging propulsion can coexist with whisper-level dynamics.

I look forward to further listening. Hamilton seems to be someone who fits into no jazz school; from what I remember, those early records are exceedingly polished, while the Impulse dates are loose and raw. Anyone know of any detailed primers re: his body of work? I'd love a guided tour.

In the meantime, here's the TONY interview, in both photo and text form:

"Backstage with… Chico Hamilton"

By Hank Shteamer; Time Out New York – September 21, 2006

You're commemorating your 85th birthday this year by releasing four diverse CDs. They include your own tunes, pieces by Duke Ellington and the Who, plus DJ remixes—why cover so much ground?

Well, that's what music is all about, isn't it? Versatility in regards to sound, rhythms and melodic structures.

One CD has a vocal cameo by Arthur Lee.

Yeah, I was really shocked when I heard that he died [in August]. I think this was his last recording. My band performed with his group Love [in the late ’60s] out in L.A., where I'm from. It was unusual for a jazz organization to share the stage with a rock group.

Speaking of your past, you worked for years in commercial and movie music, scoring films such as Roman Polanski's Repulsion. Why'd you move away from that?

There's really no such thing as a film score anymore. Everybody lifts prerecorded tracks. As for my commercial period, that was the only time jazz was played on TV. Most of the commercials were recorded by jazz musicians, who had no choice in the matter—but that work drains you, you know?

I can imagine. You teach drums and lead ensembles at the New School—what led you to that?

I realized that this could be my way of giving something back, because music has been very good to me. Schools are the only place to learn jazz today, but sadly, a lot of people teaching this music know nothing about swinging.

Okay, how do you teach someone to swing?

It takes two things: patience and fortitude. [Taps rhythmically on table] You hear that? Okay, do that for me.

[Taps along]

Good. Now can you talk at the same time?

Okay… [Still tapping] My name is Hank; I was born in Kansas City…

You're from Kansas City? Oh shit, okay! All right, keep tapping; now I want you to do this at the same time: [Sings] daaah-dah dah.

[Taps, sings] Daaah-dah dah…

See what kind of a groove you got in all of a sudden? Your whole body started to feel it, didn't it? It's just that simple, man.

Well, I actually play drums too.

That's cool. What kind of group do you have?

It's kind of a loud, heavy rock band.

Why loud? If you start loud, where you gonna go?

Down, I guess!

I think you should have some sensitivity to your sound, because the ear can only take so much.

Do you ever play loud?

I don't have no need for it. I play in the danger zone.

What's that?

It's a way of playing that's very tensified, but at a volume where you can hear everything. And I stay in that zone, with that energy happening, you dig?

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

DFSBP archives: Grachan Moncur III

NOTE (July 24, 2021): I've re-upped the links to the Grachan Moncur III WKCR interview below. If you have trouble accessing them, drop me a line at hank [dot] shteamer [at] rollingstone [dot] com, and I'll send them to you directly.

I've been listening to a lot of podcasts and online audio interviews recently. I highly recommend Jeremiah Cymerman's 5049 Podcast (I've checked out about ten of these so far, and I've loved pretty much every one), Aisha Tyler's Girl on Guy interview with Clutch's Neil Fallon, the Luc Lemay (Gorguts) and Bill Steer (Carcass) episodes of the MetalSucks Podcast, and the Lemay appearance on the Invisible Oranges East Village Radio show (click on September 3 here). While I'm not equipped to put together snazzy-sounding, nicely edited content à la what's linked above, I do have a fairly extensive archive of audio interviews, some recorded live on air. Since most of these radio shows are interspersed with music, they play like readymade podcasts. As time permits, I'll be going back through and digitizing various programs from the vaults, e.g., the 2000 Steve Lacy show I posted back in February.

Next up is an installment of the WKCR Musician's Show, featuring trombonist-composer Grachan Moncur III, that dates from less than a month after the Lacy Q&A. This has to be one of my most treasured interview tapes. As with the late, great Walt Dickerson, Moncur was an artist who existed in a kind of mythical state in my mind before I was lucky enough to be able to meet him. (I made the connection via a wonderful woman named Glo Harris—the widow of the drummer Beaver Harris—my collaborator on a memorial show concerning Beaver, which featured in-studio appearances from Moncur, Rashied Ali and Wade Barnes, and call-ins from Andrew Cyrille and Jack DeJohnette; maybe that'll be my next post from the archives!) I didn't know Moncur's story; I only knew his records, and at that time I was completely obsessed with them, especially the 1963 Blue Note set Evolution, which I still regard as one of the masterpieces of the period, and of jazz in general. Grachan (for the record, it's pronounced "GRAY-shun") and I sat down for three solid hours of talk, music and off-mic reminiscing. It was a really special experience—for one thing, I'll never forget Grachan discussing how his experience of the Kennedy assassination related to the title track of Evolution, one of my favorite pieces of music ever. I was just a kid at the time of this interview—a month shy of my 22nd birthday—but Mr. Moncur treated me like a peer. I hope you enjoy the show. Here it is, in four installments:

WKCR Musician's Show with Grachan Moncur III: 7.19.2000 - Part I

WKCR Musician's Show with Grachan Moncur III: 7.19.2000 - Part II

WKCR Musician's Show with Grachan Moncur III: 7.19.2000 - Part III

WKCR Musician's Show with Grachan Moncur III: 7.19.2000 - Part IV

NOTES:

1) The easiest way to stream these files is by clicking the Streampad link (the blue bar) you see at the bottom of the page. You can also download them as MP3s.

2) The level on the title track to Aco Dei de Madrugada (played at about the 24-minute mark in Part III) was too high, so I cut that piece from the MP3. You can hear it here. The same goes for Echoes of Prayer (featured

on Destination: Out back in 2010), announced right at the end of Part

III and continuing into the beginning of Part IV; I'm pretty sure we played the majority

of the LP, which you can hear in five parts here: I, II, III, IV, V.

P.S. I want to thank my Aa bandmate Mike Colin for reminding me of the existence of this tape. I have a fond memory of he and I going to see Grachan Moncur III play at Iridum in a band that included Moncur's old Blue Note comrades Jackie McLean and Bobby Hutcherson. They played the classic "Love and Hate" that night and Moncur took a solo for the ages. (Judging by this review, this must've been 2004.)

P.P.S. Steve Lehman's 2000 interview with McLean, recently posted at Do the Math, is well worth your time.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

DFSBP archives: Steve Lacy

I stumbled across the photo above while doing some cleaning the other day. It was taken on June 21, 2000, in the control room at the former location of WKCR, located in Riverside Church. On the left is me, age 21; on the right is Steve Lacy.

In retrospect, the regular DJ gig I held for a couple years during college was a dream. I had regular access to that incredible LP library (and to a listening audience that appreciated it); I got to learn firsthand from master broadcaster/scholar/educators such as Phil Schaap and Ben Young; and best of all, I got to interview various heroes on air, including Rashied Ali and Grachan Moncur III.

I was ecstatic to land the Lacy conversation. I remember seeing him play a few months before this: a concert with Mal Waldron at Lincoln Center's Duets on the Hudson series. I knew that the Lacy/Waldron duo would be coming to Iridium that same June, so I hung around after the show, introduced myself to Steve as a WKCR DJ, and asked if I could set up an interview in conjunction with the run. He said sure. I worked out the details with his manager, and on the appointed day, he walked up to the entrance of Riverside Church, dressed spiffily and looking a little overheated. His friendly smile put me at ease. I recall him asking for a beer, which we procured. We talked and played various Steve Lacy records on air for roughly 1.5 hours; you can listen to the program below. (You should be able to stream via the players or download by clicking on "Part 1" and "Part 2.") Some of the musical selections are included in the broadcast; you'll find a couple of the others in the Spotify playlist that follows. The opening track, which kicked off the broadcast, was "Four in One" from Reflections.

Steve, of course, sounds fantastically wise. I sound green, awkward, sometimes ill-informed. (I'm still kicking myself 12-odd years on for mispronouncing "communiqué," and for not realizing it was an English word!) If I could meet him again, I would thank him for his patience with me on that day. I apologize for the poor volume balance; you might need to adjust your levels during the portions when Steve is speaking. I chose a quieter transfer over one that would distort.

Steve Lacy - WKCR - I

Steve Lacy - WKCR - II

Click the links to download the show in MP3 form, or stream the two sections via the Streampad player at the bottom of the page—they're items 4 and 5 on the playlist. [Update, 5/15/14: Streampad doesn't seem to be acknowledging these tracks at the moment, so simply clicking the links above is probably your best bet for accessing the files.]

(Note: If you enjoy this interview, do let me know via the comments or e-mail. I have a bunch of others that I could transfer and post.)

Spotify:

Friday, October 26, 2012

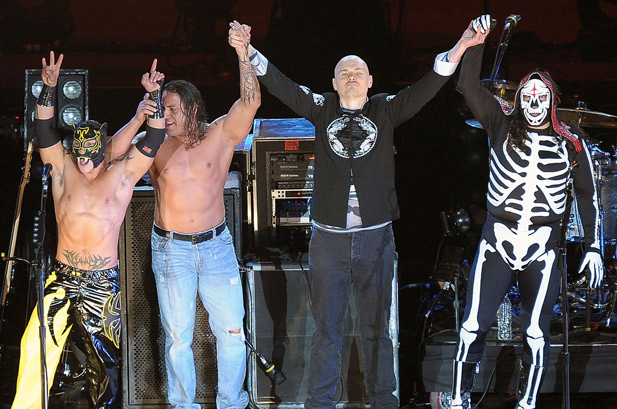

Playing heel: An interview with Billy Corgan

I recently interviewed Billy Corgan for Time Out New York. I was never a big Smashing Pumpkins fan growing up; I loved—and in many cases, love—many bands connected to the alt-rock of yore, but aside from "Cherub Rock," the Pumpkins didn't speak to me. I started hearing good things about the new SP album, Oceania, though, and when I checked it out, I found myself taking to it right away. The record is not a revelation; these SP songs sound pretty much like the ones I remember from the early ’90s. But for some reason, it was easier for me to appreciate Corgan's balance of vulnerability and bombast this time around. I admired that he was still going for an unabashedly big sound, and that he still seemed unafraid to flirt with pretentiousness in order to achieve the effect he desired. Plus, I found (and find) the material catchy as hell—concise and memorable, nearly all the way through.

In conversation, I found the man improbably charming. He's just as, shall we say, inflammatory as you might have read, but what the caricature misses is how good-natured he is about it. He seems to genuinely enjoy repartee, the trading of blows, the dropping of science. As you'll read in the interview, Corgan runs his own wrestling league. One of my favorite parts of the conversation comes when we discuss the parallels between a "bad guy" wrestler and his persona within the world of rock & roll:

"So in wrestling language, I play heel. I like to kick the shins of the Pitchforks of the world because they're pompous, and equally so, they like to point where I'm pompous. So in a way, we're benefiting from the feud."It seems to me that there's something charmingly old-fashioned about this idea. It's almost like an Oscar Wilde kind of thing. It's just hot air, he seems to be saying of his gratuitous opinion-spouting; it's just entertainment. If we seem to be taking these sorts of pop-cultural dialogues too seriously, it's only because they're more fun that way.

In short, he knows what an interviewer wants from him, in the tabloid sense. He seems to actually relish playing the part that has been foisted on him. He does it with a smile. I recently read somewhere (I really wish I could remember where) a positive reframing of the term "bullshitting," a suggestion that this kind of idle, aimless, sometimes puffed-up talk shouldn't necessarily be considered a bad thing. I'd agree with that. Sometimes we want to tune in and hear someone taking shots. The problem is, it's usually (as on reality TV) cast in a dead-serious light. With Corgan, it's all about mutual amusement. I had a blast talking to him.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

A chat with ?uestlove

A couple weeks ago I had the pleasure of interviewing the drummer, bandleader and all-around music fiend ?uestlove. We talked in his tiny drum booth, part of a makeshift recording studio adjacent to the Jimmy Fallon set. I sat in a corner, and ?uestlove sat behind his kit, politely facing away from me so as not to spray me with crumbs from the kale chips he was snacking on.

A condensed version of the conversation appears in the next issue of Time Out New York, an advance plug for the Shuffle Culture event that ?uestlove's curating at BAM Thursday and Friday, April 19 and 20. The online cut of the Q&A, which you can read here, is about twice as long.

I'll admit that I'm no expert when it comes to ?uestlove's massive body of work. Much of what I know of the Roots and his various side projects and production jobs comes from the 24 hours of cramming I put in prior to the interview. But every time I've ever heard him play, watched live clips (I wish I could find that vid of him nailing the opening fill on Elvis Costello's "(I Don't Want to Go to) Chelsea") or read interviews, I've always been impressed by the sleek economy of his drumming and the unpretentious wisdom of his R&B/hip-hop scholarship. ?uestlove's career is a lesson in how to become a pop star without compromising your integrity or sacrificing the core music-nerd-hood that made you cool in the first place. I had a blast speaking with him.

P.S. There's way more to the conversation than you'll read above. I hope that eventually I can get around to posting a few outtakes here. For one thing, he offered up great anecdotes re: attending high school with heavyweight jazzers like Kurt Rosenwinkel and Christian McBride.

Saturday, January 14, 2012

Heavy Metal Be-Bop #6: Bill Laswell

I'm happy to report that Heavy Metal Be-Bop, my jazz/metal interview series, has returned from a little hiatus. The sixth installment, a Q&A with Bill Laswell, is live in abridged form at Invisible Oranges (metal is the focus here, of course) and in a greatly lengthened director's cut at the series's online home, heavymetalbebop.com. (HMB #7 is already in the can, though no promises re: how soon I'll be able to post it.)

As I mention in the intro to the Q&A, which you'll find at the links above, it's hard to discuss the jazz/metal connection without bringing up Bill Laswell; along with John Zorn, he's an elephant in the room. You'll find some Laswell talk—specifically, comments on Last Exit, the polarizing ’80s improv quartet he worked in with Peter Brötzmann, Sonny Sharrock and Ronald Shannon Jackson—in two prior HMB installments; check out Melvin Gibbs's thoughts here and Craig Taborn's here.

I'm not sure when I first heard of Bill Laswell. I remember that my teenage interest in Mick Harris's idiosyncratic dub-metal project Scorn (I still love the Evanescence LP) led me to the Laswell/Harris collaboration Equations of Eternity, and that a review in the sadly departed metal rag Rip tipped me off to Painkiller, Harris and Laswell's avant-grindcore trio with John Zorn.

As I got more into both jazz and metal though, I developed something of a distaste for Laswell. I remember being immensely excited when I first learned of the existence of 1997's The Last Wave, a trio record with Laswell, Derek Bailey and Tony Williams (!) under the collective name Arcana, and of Last Exit itself. Being a Bailey and Williams nut, as well as a Sharrock obsessive, it seemed that I couldn't go wrong with this material (not to mention Material, a Laswell project that featured guest turns from Sharrock and a bunch of other free-jazz heroes set against a backdrop of off-puttingly synthetic—for me, at least—’80s art-dance). But in the case of The Last Wave, the strange, boomy production, and in the case of Last Exit, a funk-oriented bass presence that struck me as a sore thumb, kept me on the outside. Records like these were classic examples of "On paper, this looks tailor-made for me, but I just can't get with it in the flesh."

Over time, though, I realized that I couldn't stay away. I wasn't going to let my aesthetic quibbles keep me from savoring some of Tony Williams's final recordings (the drummer died during the making of the second Arcana record, Arc of the Testimony), or an extended series of exchanges between musical heroes of mine such as Brötzmann and Sharrock. The more I sat with the Laswell discography (or at least the wings of it that intrigued me most), the more it impressed me. What I realized was that, like John Zorn, another artist whose own work I have mixed feelings about but whose curatorial/community-forging instincts I admire greatly, Laswell's greatest achievement has been his bridge-building, his willingness to forge connections between artists who never would've found each other (note Herbie Hancock and Akira Sakata's names on that Last Exit LP jacket above), or at least probably wouldn't have thought to document their meeting on record: Bailey and Williams, say, or Keiji Haino and Rashied Ali (who appeared with Laswell in a collective called Purple Trap), or Sharrock, Brötzmann and Shannon Jackson, who seem like soulmates after the fact but who, to my knowledge, hadn't played together before Laswell convened them. The Praxis project is another example; I'm not in love with the later material (oriented around Buckethead and Brain), but it warms my heart to read the personnel list for 1993's Sacrifist, which includes Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell alongside the dudes from Blind Idiot God. Laswell's work as an intergenre unifier is less well-documented than Zorn's (in founding Tzadik, Zorn created an invaluable umbrella entity that Laswell never managed to maintain for an extended period), but it's equally undeniable. I'm thrilled that these records exist.

And to branch out briefly into Laswell's work as a producer, the musical world owes him a great debt for helping to resurrect the career of Sonny Sharrock. Guitar and Ask the Ages are among my most treasured records, period, the two best presentations of Sharrock's heartrending magic. (Seize the Rainbow, a Laswell co-production, is an idiosyncratic keeper as well.)

Part of the fun of the Heavy Metal Be-Bop series has been interrogating some of my old aesthetic prejudices. To ignore Laswell outright would a major self-disservice. Just as I don't love all of his records, I don't agree with everything he has to say in the conversation linked above (for one, his estimation of Dave Lombardo's limited musical scope seemed overly dismissive, and even disrespectful), but I'm grateful to have had the chance to sit down with him and discuss this strange musical nexus. Tony Williams, whom Laswell knew well and worked with often, acted as a fulcrum for the conversation, and I think we ventured into a fair amount of underexplored territory re: Williams's ambitions and aesthetic goals as a rock-oriented player.

I hope you enjoy the interview. I'd like to sincerely thank Mr. Laswell for taking the time to meet with me.

Monday, October 24, 2011

Loutallica speaks

I was fortunate enough to interview Lou Reed and Lars Ulrich for GQ. (Many thanks to Will Welch for the opportunity.) You can read the transcript here. As several have commented, yes, Mr. Reed was intent on giving me the third degree; that's okay—it made for a lively interview. Mr. Ulrich, on the other hand, was a sweetheart—one of the more patient, thoughtful folks I've had the opportunity to speak with on the record.

The occasion is, obviously, Lulu, the new Reed/Metallica collaborative LP. Folks are already lining up to drub this release, and that saddens me a bit. The fact is, it's a significant work that deserves your time and effort. I only got to hear it twice before my interview, and the first time through, I was put off by it; it seemed underorganized, underedited—a failed experiment. On the second spin, though, I felt differently: This big, shaggy thing started to cohere, and I began to admire the ballsiness of the endeavor. Lulu is awkward in spots, and it is in many ways a taxing listen, but it is emphatically not crap. Spend some decent time with it before you write it off.

I think this record is going to be an interesting litmus test: I can see Metallica die-hards hating the Reed aspect, and Reed fans scoffing at Metallica's contribution. Who is it for then? I'm not really sure, but I admire the follow-through all the same. As far as my own perspective, I'm obviously a lifelong Metallica freak, but Lou Reed (both solo and with the Velvet Undeground) has never really clicked with me. I relished the opportunity to try again in preparation for this interview, and I found a few records that really spoke to me, including The Blue Mask and, yes, Metal Machine Music. My opinion of Lulu is still in flux, which is a good thing; the highest compliment I can pay the record is that I'm excited to spend more time with it.

Why not listen for yourself?

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

Bill Stevenson on jazz

I have a Post-It on my wall labeled "dream interviews." There are six names listed, four of which are crossed off: Glenn Danzig, Cecil Taylor, Richard Davis and—the latest—Bill Stevenson, whom I interviewed a few weeks back for Time Out New York. (Trey Azagthoth and Charles Brackeen are left!) Stevenson, the drummer of Descendents and ALL, as well as a former member of Black Flag, was far friendlier and more enthusiastic than two of the other names on the list (I'll let you figure out which). I've been a fan for years, and I wasn't let down in the slightest by our conversation.

Important points:

1) The Descendents play Roseland Ballroom in NYC this Friday, September 23. Info via TONY.

2) Here, via the TONY site, is an edited version of the Bill Stevenson Q&A. Topics-wise, this is much more accessible than what's below; among other things, we discussed Stevenson's recent health problems and his ever-evolving impressions of several classic Descendents songs.

3) Below is an extended outtake from the chat dealing with Stevenson's interest in jazz. We touched on Black Flag's instrumental/improvisational experiments, Stevenson's love for Ornette Coleman and quite a bit more.

/////

HS: With regard to Black Flag, I'm really interested in the instrumental material and some of the more improvisational stuff, like on The Process of Weeding Out and Family Man. Did you feel like there was a current of, for lack of a better term, punk fusion that you wanted to explore further that got cut short?

BS: Yeah, I just wish I was a little further along as a musician when we were trying to do that stuff. 'Cause I was listening to Charlie Parker, listening to Ornette Coleman, listening to the Mahavishnu Orchestra, listening to King Crimson, but I didn’t quite have—even with respect to my meter, my ability to hold time while doing various improvised things—I just wish I had been better when we were trying to do that because I think it could have been more successful. We could have found maybe a whole other bunch of people that might have enjoyed it. I very much appreciate the fact that we were trying to do what we were doing, but I don’t necessarily think the execution was on vinyl as it was in our heads.

HS: It was almost like the first stab at something like that, that had been attempted.

BS: Well, I mean, with guitars, you know, but Ornette Coleman was doing it for 25 years.

HS: Sure, but coming out of a hardcore vocabulary.

BS: Yeah, but we weren't paying attention. It didn’t matter what 7 Seconds or whatever was doing. It just mattered whatever we were interested in at the time.

HS: I was reading an interview from 2003 where you were talking about that rumored ALL instrumental album. You mentioned that you guys were getting into this more improvisational style and had encountered some difficulties in playing that way. Has that current been picked up? Have you been working on that instrumental or improvisational material?

BS: We recorded seven pieces, four of which I think are pretty good, but yeah, it’s just one of those things where, you know, the rent is due, so do we have ten hours a day to apply to this? Functional concerns are obviously the number one enemy of creativity. I don’t know; I don’t have a logical answer.

HS: You were saying how back in '84, you didn't feel like as a player, you were quite up to the challenge of exploring that kind of improvisational stuff with Black Flag. Did you undertake a serious study of jazz or fusion after that?

BS: Oh yeah, you’re damn right I did. I think one of the cooler actual success stories of that would be maybe the song "I Want Out" on Problematic by ALL. It’s not on the improvised side, but on the unfathomably technical side where you can still sing along. And then another one would be the song "Virus" on the Only Crime record To the Nines. There's a middle section in that song where for me it’s interesting because it’s like a drum improvisation over a set pattern—kind of the opposite of bebop. So I’ve had a few things that I would consider to be successes in that area. But I don’t know… Improvising is like… Guitar solos are like farts. They’re okay if they're you're own, but who necessarily wants to listen to them?

HS: Well, what I really like about some of the more experimental Descendents material is that you’re right on the edge. The Process of Weeding Out is freer, like the bass and drums are holding something down while the guitar goes off. But what I like about something like "Uranus" by the Descendents is that it’s a composition. It has a looseness and a little but of space in it, but it’s still a written piece of music.

BS: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Your perception of this is right on. That's what I mean. I think "Uranus" is a success story in this way and maybe that song "Birds" on ALL's Percolater. There have been a few successes. So I think you might like that song "Virus" on the To the Nines record by Only Crime. That’s in a different way though because it has vocal patterns and everything.

HS: Especially ALL during the period of Allroy Saves, I almost feel like it was this new kind of progressive rock, where all the ideas that would be in a Yes song or something like that would be squeezed into these one-minute songs.

BS: Uh-huh, yeah.

HS: Like that song "Check One," which I've always thought was a mini masterpiece that you wrote. Do you remember anything about how you came up with material like that? Can you give an insight into what you guys were drawing on with a song that complex?

BS: There’s just the obvious kind of five things I suppose, which is Ornette Coleman, Charlie Parker, King Crimson, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Zappa. You know, they’re kind of ordinary influences, but you know how this stuff works. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and it all depends on what it is you’re listening to when when you’re listening to this stuff. Even with Miles Davis, I reckon there’s 50 different ways you could listen to Miles Davis and be getting 50 different things out of it, and that’s certainly true with Ornette.

HS: Do you have a favorite period or couple records of Ornette?

BS: Oh, fuck… He’s my all-time hero of the world, so I don’t even know where to start. I think that most of that material—the chronology escapes me, and this is part of the function of the neurosurgery is some of my memory for minutiae is not all the way reassembled, but I'm gonna say this: All the way up through those releases that they repackaged as Beauty Is a Rare Thing, everything up through that are my eight favorite albums. And then after that, I like the Science Fiction sessions. Oh God, fuck! You what I love? Skies of America! Nobody likes that one, but I love that one.

Ornette to me reached a point where you’d put on the record and it would sound like in high school, in the band room before the teacher got there and everybody was warming up and tuning up—that sound. Sometimes Ornette's records sound that way, and I can’t quite handle that but when it doesn’t sound like that, then it’s my favorite thing in the whole world. And I even like his—I’m gonna call them straighter bebop records, those first two: Something Else!!!! and Tomorrow Is the Question. I love those more than The Shape of Jazz to Come, but then the ones after The Shape of Jazz to Come are some of my favorites.

HS: Like This Is Our Music or Change of the Century?

BS: Yes!

HS: Would you be able to describe specifically how you’ve been influenced by, say, Ed Blackwell or Billy Higgins? Or do you think it even works that way?

BS: I reckon drumwise, from that arena, I would see more of an Elvin Jones influence. Or I saw Ornette a few years ago and he had his son on drums. I’ve grown to love Denardo but I don’t know… Then it was a bow bass and a finger bass and Ornette. Man, I couldn’t even breathe I was so… It was amazing! I know this doesn't sound like anything to you, but I live in Fort Collins, CO, so I don't get to see Ornette. That same year, I got to see McCoy Tyner just a couple months later, and I was like, "Yes!"

HS: Was there a period where you were gigging as a jazz drummer? Or was it more like private study?

BS: No, that would be the hugest mistake or oversight, would be to try to put me in that category. I simply don’t have the chops. I more just try to sneak in a little bit of the wonderment or elation of musical discovery that is occurring in real time when jazz musicians are playing. I love that.

HS: I play drums as well, and I sometimes feel like it's almost impossible for a drummer to be truly great at playing both rock and jazz. Do you think you have to pick one of the two and focus on that?

BS: I think so. What I was trying to do was to be both. I reckon Billy Cobham is maybe the closest: He's the everyman's drummer, like he can playing everything better than everyone. And I felt like I was heading that direction—maybe I wanted to be Billy.

But then there's the stick-size issue. I use, like, Sequoia tree trunks in, say, Black Flag, and then if I’m trying to play jazz, which I usually just do by myself, then I’m using really small sticks. So I have this medium-size stick that I use so that I can … I don’t know, it’s like being a jack of all trades, master of none. So now the rock stuff’s not as heavy, but the jazz stuff still isn't fast enough. Those are the things we think that when we sit down at the drums everyday, those are the things we struggle with: Who do I wanna be? How do I wanna define my style? Or do I even wanna define my style? What kind of mood am I in today? Today, I’m gonna play with the 7As. Tomorrow, I'll whip out the DC-17s, and we’re gonna go that route. Or maybe just 5 minutes later we’re going to whip out the DC-17s.

HS: Yeah, I always think about someone like Tony Williams. When he’s playing fusion, it sounds really good but it doesn’t sound like a great rock drummer; it sounds like a great jazz drummer playing that way.

BS: Yeah, I think we all want to be that guy that can just do everything better than everyone, but sometimes it's fun for me to just do my—I have my eight things that I can do better than anyone in the world—just do those. I’ve got my one little, stupid drum roll that I do on every song and my stupid surf beat, and that’s me without thinking, just on instinct and in a way, that’s home.

Thursday, June 02, 2011

In full: An interview with Peter Brötzmann

About a month ago, I spent one and a half hours on the phone with Peter Brötzmann (from midtown Manhattan to Wuppertal, Germany). I've carried on in recent posts about my intermittent addiction to this man's music. For about a decade now, his sound has functioned for me like a somewhat exotic favorite cuisine: not something I'm always in the mood for, but when I am, I won't settle for anything else.

Mr. Brötzmann was a delight to talk to. (At this point, I'd like to extend a hearty thank you to Patricia Parker at Arts for Art for setting up the interview, which was Time Out New York–backed and timed to Brötzmann's June 8 appearance at Vision Festival XVI.) It would be somewhat absurd to expect a creator of extreme and often violent music to also express these qualities in conversation, but it didn't seem out of the question that Brötzmann might be a bit brusque or no-nonsense. Actually, he was unfailingly warm, totally unhurried, funny, reflective, occasionally profane. In short, I got a constant "I'm talking to a really good guy" vibe throughout our interview. It made me wonder why I hadn't read more interviews with the man before. After all, he tours the world regularly; you'd think that press folks would get curious and request Q&As. Whatever the case may be, I felt completely elated during and after this experience. I almost always enjoy the interview process, but this one seemed to be in a class of its own.

I feel that the results will be of interest to Brötzmann fans, which is to say that they were/are of interest to me, i.e., I learned a lot about him and clarified a lot more. Just to cite one example, I've always been fascinated by Brötzmann's inimitable verbal sense (Nipples! Balls! Hairy Bones!), and he spoke candidly about this:

"If you take Balls or Nipples, the sexual side of the music, you have it in rhythm & blues as much as you can. It's very important, and was and still is for me."

That's just a small snippet. If you have a chance, please check out the interview and let me know what you think. If you're new to Brötzmann, I suggest starting with the profile piece that the conversation fueled.

I should mention that this Brötzmann interview was just one component of an NYC-jazz package created for the Time Out New York website by myself and my esteemed colleague Steve Smith, whom you might know as @nightafternight. In addition to a calendar of the top jazz shows for the coming summer, you'll find our thoroughly subjective list of 25 essential New York jazz icons of the present moment. (DFSBP regulars might be able to guess who my No. 1 pick was, a pick at which Steve and I each arrived at independently.) As with the Brötzmann materials, I welcome any feedback regarding this list. I had a blast working on it, but it was definitely an eye-opener in terms of my own biases and blind spots.

P.S. I encourage all Brötzmann fans to visit his new shared web home, Catalytic Sound, where you can buy records direct from the artist.

Monday, March 21, 2011

Ween outtake: Q&A with Eye of the Boredoms

Last night's release party for my Chocolate and Cheese book (available on Amazon starting 3/31) was a blast. I'd like to extend a sincere thank you to WORD for hosting, to Tom Kelly and Laal Shams for remedying some last-minute technical issues, to Claire Heitlinger for providing the chocolate-and-cheese refreshments, and to everyone that came out.

Two more release events are coming up soon:

Saturday, March 26, 2011 at Farley's Bookshop in New Hope, Pennsylvania. 1–4pm

Thursday, April 7, 2011 at Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. 7:30pm. Also appearing: fellow 33 1/3 authors Daphne Carr (Nine Inch Nails' Pretty Hate Machine), Christopher R. Weingarten (Public Enemy's It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back) and Bryan Charles (Pavement's Wowee Zowee).

By way of a countdown to the book's official release, I thought I'd post some interesting odds and ends from my research that didn't make it to the final product. Below is an exceedingly brief interview with Boredoms mainman Yamataka Eye. I tracked down Eye due to his involvement in the little-known record Z-Rock Hawaii, a collaboration between him and Ween—with trusty producer Andrew Weiss along for the ride—that was made right around the same time as Chocolate and Cheese, i.e., somewhere between the fall of ’93 and the spring of ’94. (I remember reading somewhere that though several members of the Boredoms are credited on the record, it was only Eye that actually appeared on it—I can't find the source now, though, so don't quote me on it.)

Z-Rock isn't a great album, but it is a fun one, a meeting of the deranged, outsider-pop minds. Much of the record skews toward inscrutable yet hilarious sound collage (e.g., the immortal "Tuchus") and high-speed, drum-machine-fueled spaz punk (e.g., "Love Like Cement", where the Ween-plus-Boredoms angle really comes through). But my favorite track is "God in My Bed" (streaming above), an atmospheric spoken-word piece that plays like an account of a drug-induced meltdown thanks to a muggy drone background, commentary from a lonely trumpet, some trademark Ween slowed-down-voice action and a deeply disturbed monologue. I love the robot-malfunction "scramble" effect on the vocal at 2:06 and the genuinely creepy conclusion (3:16), which reminds me of John Goodman's climactic rant in Barton Fink: "You want my chicken? My potato salad? You want me to tell you how my day was?!?"

As far as the Eye interview, it was probably the most least profitable Q&A I've ever undertaken, in terms of usable material generated vs. effort expended. (That's just a factual statement, no disrespect intended: That's why they call it a language barrier.) When I reached out to the Boredoms camp, I was told that I could interview Eye over e-mail but that I'd need to have my questions translated into Japanese before sending. Furthermore, the answers would be sent back to me in Japanese, so I'd need to get those translated back into English. A journalistic nightmare to be sure, but I found a friend of a co-worker who was willing to help me out. When I finally got the English answers back, though, they were so brief that I didn't see any way to incorporate them into the manuscript. Oh well, it was an interesting detour in my research. Also, looking back at the Q&A, I realized I'd forgotten how much I loved Eye's answer to my last question...

/////

Eye Q&A re: Z-Rock Hawaii—August, 2009

How did the Z-Rock Hawaii project come about?

I don’t remember exactly, but I loved Ween so I was really excited when they talked to me about it.

What do you remember about working with Ween? How was the music composed and recorded? Did you actually perform in the same room with them?

I was staying at Mickey’s house. I’m pretty sure it was the house they called “The Pod." Andrew was the engineer. I don’t remember exactly how we wrote the songs, but I remember it being fun.

Were you a fan of Ween before you met them? What do you enjoy about their music?

Of course I was a fan. There’s something natural about their music. Something really laid-back and spontaneous.

Since Z-Rock Hawaii was recorded around the same time as Chocolate and Cheese, do you remember hearing anything from that album before it was released? If so, what was your opinion of the material?

Unfortunately I didn’t get a chance to listen to it back then.

Do you have any other impressions of Chocolate and Cheese? Was it influential to the Boredoms at all?

I’m not sure. I really love it, but I don’t know if it had an influence on the Boredoms.

Do you notice any general similarities between Ween and the Boredoms?

Maybe it’s that we’re all geeks? (I hope that doesn’t sound rude.)

Monday, November 01, 2010

Dead-ass doin' it: Phil Lynott, Nicki Minaj and other pop chameleons

Time Out New York: Do you think you can still be believable singing a sweet love song after you’ve done all that [raunchier material]—?The above was one of my favorite exchanges from a really enjoyable conversation I had with Nicki Minaj on behalf of Time Out. (Check out the full Q&A here if you have a sec.) The sentiment she's expressing—the weird dual personality that's required of a pop star, and the unflappable confidence needed to pull it off—has been ringing a bell with regard to my current listening obsession: Thin Lizzy.

Nicki Minaj: Absolutely… I’m believable at whatever I do, because I’m dead-ass doin’ it.

The other day I finally watched The Rocker, a doc about the late Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott that I'd had lying around for a while, and I found myself newly impressed by his versatility. As with Ms. Minaj, whatever he did—whether it was a nakedly sentimental love song, a streetwise picaresque or a sleazy come-on—he was thoroughly convincing. Ludicra and Hammers of Misfortune guitarist John Cobbett eloquently summed up the core paradox of the man in a fine recent Invisible Oranges interview (a quote brilliantly excerpted by Inverted Umlaut): "Phil Lynott is the ultimate lyricist for the tough guy with the broken heart."

Today I've been spinning the outstanding 1979 Lizzy disc Black Rose: A Rock Legend, and I'm somewhat shocked by the sheer variety of emotions expressed here. There's one of Lynott's classic paeans to gritty urban life ("Toughest Street in Town"), a weirdly moralistic meditation on kinky sex ("S&M"), a determinedly sappy yet utterly charming tribute to his daughter ("Sarah," see above for a mind-blowing über-lounge rendition, complete with time-lapse-aging model stand-ins), a rueful I'm-through-with-the-bottle lament ("Got to Give It Up") and a half-crazed romantic kiss-off ("Get Out of Here"). I'm not yet through the concluding title track, but I'm prepared for another left turn.

In a weird way, this wanton versatility, the sheer disregard for emotional continuity, reminds me a lot of Ween's masters-of-disguise approach to album-craft. The message is that of all great pop (from Black Rose to Chocolate and Cheese and beyond): Each song is its own universe; live in this feeling for these three minutes. And maybe when that time has elapsed, you'll be transported in an instant to somewhere completely different. It's the same chameleonic impulse that allows Nicki Minaj to sass her way through "Itty Bitty Piggy" and then dreamily croon "Your Love" in the manner of a doe-eyed teenager. As fans, we're okay with the contradiction—as long as, like the great Phil Lynott, whatever the artist in question is doing at a given moment, he or she is indeed dead-ass doin' it.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Listen to this: Francis and the Lights

I'm very psyched about Francis and the Lights right now. Go here to read my TONY profile of the band's leader, Francis Farewell Starlite, and go here to read a marathon transcript of the entire interview, in which we discussed his recent tours with Drake and MGMT, his admiration for Anthony Braxton (with whom he studied at Wesleyan), the fine art of saying no and much more. Also, I highly recommend that you (a) listen to the new Francis and the Lights album, It'll Be Better; (b) watch the new Francis and the Lights video; and (c) go see the band live either tonight (Thursday, August 12) at S.O.B.'s or next Tuesday (August 17) at Radio City Music Hall with MGMT.

Monday, April 05, 2010

In full: Xiu Xiu's Jamie Stewart

Very happy to be able to link to my hot-off-the-press profile of Xiu Xiu on the TONY site, as well as the full transcript of my conversation with bandleader Jamie Stewart on the Volume. Re: the former link, don't miss the list Stewart compiled at the end of five albums that scare him: a classic assortment of the perverse and/or extreme, with records by Cecil Taylor, Diamanda Galás and more. Speaking of Taylor, jazz heads might be interested to hear Stewart's further thoughts on the maestro, which come right at the end of the unedited Q&A.

If you haven't heard Xiu Xiu, I'd probably recommend The Air Force, which landed on my 2006 top ten list. Imagine an almost surreally perverse Casio-fueled version of Scott Walker, only with much catchier choruses, and you'll get some idea of the strangeness and intensity of this project. The new album (Dear God, I Hate Myself) is outstanding, and you can hear it via that first TONY link above. For the totally uninitiated, The Air Force's "Boy Soprano" is probably my favorite Xiu Xiu 101 track.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

RIP Walt Dickerson

The great vibraphonist Walt Dickerson has passed away, according to the following message circulated by drummer Andrew Cyrille, an important collaborator of Dickerson's:

"To all concerned:

I was asked to inform you of the regrettable death of vibraphonist,

Walt Dickerson, by his beloved wife, Elizabeth. Walt passed away on May 15

from cardiac arrest. He was 80 years of age and lived in Willow Grove, PA.

In sympathy,

Andrew Cyrille"

*****

As some readers might remember, I've been fascinated with Dickerson's music for some time, and I was lucky enough to to spend an amazing afternoon with him back in '03. Here you can find the full transcript of our conversation:

Walt Dickerson interview - 6/29/03

Part I

and

Part II

My JazzTimes piece that resulted from this interview can be read here.

Strangely, just last night I came across a download of Dickerson's Tell Us Only the Beautiful Things LP. This was the only Walt album I was unable to track down back when I was researching the story; can't wait to dig into it.

It's very, very sad that Dickerson never emerged from his silence to record again. When I spoke with him, he told me he was still playing every day...