The debate over the now-infamous "Sonny Rollins"

New Yorker piece continues. I'm not going to get into what I think of the original article, or the points made by its various supporters and detractors, or even Sonny's own response, mainly because I think both the incident and its aftershocks are beside the point. That point being: music ("jazz," or what have you) as an actual human practice, happening now, in real time—rather than an idea to be lobbed about abstractly.

I bring up the Sonny business mainly because I read Justin Moyer's jazz-bashing

response in The Washington Post yesterday, and then went out to see a very satisfying night of what you might call jazz—the

Aum Fidelity–backed double-record-release bill of Darius Jones and Matthew Shipp and the Farmers by Nature trio (Craig Taborn, William Parker and Gerald Cleaver, pictured above, left to right) at ShapeShifter Lab; and a trio set by Travis Laplante, Mick Barr and Nick Podgurski in a Clinton Hill living room, part of the

Home Audio series. One of Moyer's points ("There’s not much difference between a screechy performance by avant-garde saxophonist Peter Brötzmann

from 1974 and one

from 2014") stuck with me—the idea being that "free jazz" always sounds the same. I've seen enough supposedly free performances to know that, when it comes to the post-Coltrane/Ayler tradition, at least, "free" can indeed refer to a well-rehearsed script. I happen to love Peter Brötzmann—’74, ’14, whenever—and I think he's a much better listener/collaborator and more diverse performer than he's given credit for. But yes, you go to see him, and you know that a certain flavor of ornery, macho catharsis is going to be part of the deal.

But I take issue with the idea that actual freedom, actual improvisation, is a myth, and that, to cite another one of Moyer's points, improvisation is overrated as a rule. Again, I agree with him in the macro sense. Moyer writes, "…the fact that music is improvised doesn’t make it great." Amen to that—I think the idea of improvisation (or any other philosophical construct that informs music's creation or performance, be that serialism, or graphic scores or Conduction, or what have you) being presented as an inherent virtue of that given piece of music is b.s. I'm really only interested in the result, and very often

songs, or more generally, compositions, are what I'm after. As a metalhead, I love riffs; as a jazz guy, I love melodies—Ellington, Mingus, Andrew Hill, etc.; as a lifelong pop fan, I love hooks.

But, in some cases, improvised music appears before you as a kind of miracle. Watching Farmers by Nature last night, I felt like I was witnessing the honest-to-God creation of something out of nothing. It wasn't free jazz, or any other kind of calcified thing. It wasn't self-important about its method. It was just an honest shot at doing what improvisers ought, ideally, to do every time, which is not simply to empty your closet of every idea you might have stuffed in there, but to deal with the moment, with its possibility, and to listen, really listen, to what your collaborators have to say, and concern yourself with supporting those ideas, as well as the overall continuity, as fragile as a bubble, of the collective statement.

The set had a real elegance of design to it. Parker started out solo, and the other two slowly built up a kind of murky groove, rising out of nothingness. From there, over roughly an hour, the music visited roughly six or seven different zones, like track demarcations on an album. Each proceeded logically from the one before, and never arrived till the group had fully explored the prior area of inquiry. I remember an episode of fractured funk, with Taborn and Cleaver clanking out jagged accents, completing each other's sentences; an exquisitely chill section that felt almost like placid bossa nova; a couple of frenzied Taborn flights, where he came off like a short-circuiting cyborg, juxtaposing single, percussive notes from different registers of the keyboard; a long unaccompanied Cleaver solo that took full advantage of some expert tom-tom tuning—the drum kit was really singing, in the melodic sense—and ramped up to torrential density; and maybe most profound of all, a section featuring Parker on arco. I don't think I've ever heard a double bass cry out with such grain and elegy and deep feeling as it did last night in Parker's hands. Taborn accompanied with superhuman restraint, serving up quiet yet extremely resonant chords.

So, yes, sensitivity and restraint are a big part of why this music succeeded. But as I attempted to describe above, the group raged plenty as well. I think what impressed me so much was, again, this sense of continuity, of each player's—and the trio's, as a collective unit—awareness of the overall arc. Too often, long sets of improvised music follow a predictable quiet-loud-quiet shape. This felt more like a suite, with each movement taking on its own special mini contour. The band went for the climax when it was there, but they never milked it. Intensity was only one color on the palette. And the same goes for the hierarchy of the music, as it were. For long stretches, the band played in a way that seemed totally collective, i.e., sans soloist, almost in the way that groups like the Necks improvise. But, as with the varied dynamics, collectivity was just one strategy. During plenty of other moments, the more traditional soloist-plus-accompanists concept was very much at play. Each of the three players starred in turn.

Most amazing to me, though, was how the moment, the actual spontaneous unfolding circumstance, seemed to drive the set, as much as the will of any one player, or even of the trio as a whole. I'm thinking, for example, about how Gerald Cleaver's smallest cymbal—the size of a splash, but with a more ping-y, less tinny sound than I've often heard out of splashes—turned out to be something like a central character during the last 10 or 15 minutes of the set. Throughout the performance, Cleaver moved this cymbal around the kit—sometimes it was perched on its own stand to his right, sometimes it was resting on the hi-hat stand above those cymbals or on the floor tom or snare. So, in the middle of one such transfer, Cleaver happened to drop this little cymbal. He reached down beside the bass drum and picked it up, and then he went to put it back on its original stand to his right. But this act became, in and of itself, a sort of tic or weird fixation. He didn't just replace the cymbal and go on playing the full kit. He began obsessively, continuously spinning the cymbal around on the stand, eliciting a faint little creak. The other players didn't seem to directly respond, but as Cleaver turned the cymbal around and around, it was almost like he was drawing the accumulated momentum of the set down into a final moment—draining the water from the tub, funneling the creative material out of the air. Taborn and Parker gradually quieted, and Cleaver was striking the still-spinning cymbal with a wire brush, almost inaudibly. He stopped spinning it and continued whacking the brush into the air, engaging in movement but producing essentially no sound. And that was the end of the set.

I trust that none of the above episodes, the high-intensity Taborn solos, the Parker arco feature, the concluding Cleaver small-cymbal mini drama, were planned. Befitting their group name, the three musicians actually were harvesting moments, turning them over, wringing out all their potential. The overall result didn't sound anything like any stereotypical idea of "free jazz," or any other style of improvised music I can think of. But at the same time, it wasn't alien; it felt fully logical, narrative, directed, harmonious, complete. The set lasted for exactly the right amount of time, and for the band to have played a single note after the ending would've felt (to me, at least) superfluous. This Farmers by Nature set wasn't great because it was improvised; it was great because of, as I've attempted to describe, the brilliance of the various individual moments and the coherence of the overall form. At the same time, I think the set's uniqueness, the fact that what happened last night hasn't happened before and won't happen again, was part of its immense appeal. We shouldn't fetishize the means of production—how something was made, or according to what principle—but when something truly special arises from a certain method, or lack of method, it's good to remember that, yes, that method has potential. It is absolutely no guarantee—not whatsoever—but improvisation

can, under certain circumstances, take both players and audience somewhere they've never been. Last night's Farmers by Nature set reaffirmed that fact for me. As always, I'll be staying tuned.

/////

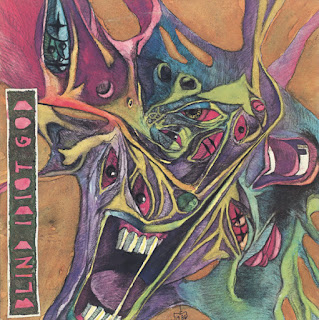

P.S. My focus on the Taborn/Parker/Cleaver performance isn't intended to slight the other sets I saw last night. Both were fierce and beautiful. Darius Jones and Matthew Shipp burrowed ever further into the special kind of poignant, stormy melancholy—doled out in three- or four-minute chunks, the so-called Cosmic Lieder of their album titles—they've been creating as a duo

for the past few years. And Travis Laplante and Mick Barr, both scarily extreme, virtuosic and idiosyncratic musicians, unleashed their respective aesthetic selves, but with no sense of autopilot whatsoever, building something collective and response-based, with help from Nick Podgurski's expertly tension-ratcheting percussion, moving imperceptibly from sparseness to brutal density. A hell of a night all around.